Notes

HOW TO ANALYZE MUSICAL STRUCTURES

Composers throughout the ages have acquired valuable insights into the compositional process by looking at the music of their contemporaries and predecessors. A great deal of their education is spent listening to music and studying scores. Early in their careers, all composers employ a good deal of imitation because, in our business, it traditionally is the greatest form of flattery. When we hear something we like in someone else’s music we want to use it in our next composition. The goal of every composer is to move beyond the period of imitation to a discovery of his or her own individual voice. No composer was ever completely original because no one grows up in a musical vacuum. No one ever learned to be a composer from reading a book. Budding composers learn their craft by working with an experienced teacher who can evaluate the myriad subtleties of the compositional process and offer valuable suggestions and corrections.

The Waring Blender Theory:

It is my contention that what we think of as original compositions are, in fact, only 5% original at best––that producing a personal style is like adding different ingredients together in a blender. 95% of what we call personal style derives from what we have absorbed from outside influences. To this mixture we add a touch of our own uniqueness. By throwing the switch, the blending process homogenizes all these ingredients into what we think of as originality.

If you are not curious about how music is put together, stop here and close the book. The reason we analyze music is to find out how the music we enjoy listening to is constructed––to tell us why it sounds the way it does. The process of analysis involves the labeling of agreed upon components as well as the interpretation of the relationship of these materials to one another. As analysts we must try to get inside the piece to see what makes it work the way it does. Every compositional process is a mind game that the composer plays with himself. Every game has an objective, game pieces, rules, and moves. The intellectual joy of every theorist is to postulate about what kind of game plan a certain composer may have employed in the act of writing a particular piece. The interesting thing about music composition is that although there are general stylistic guidelines which composers in particular periods seem to follow, each piece of music is a unique collection of compositional choices. Therefore, from the study of many individual pieces comes an understanding of general compositional strategies as well as an appreciation for those special moments of unexplainable genius.

Structural units

Structural units

The first job of a theorist is to address the question of musical structure––just how are the sounds and silences of a musical composition organized? There is nothing simple or obvious about it, as any beginning composer or analyst has discovered. There are innumerable problems of musical syntax and grammar that must be learned through much hard work. One begins by analyzing simpler pieces, such as folk songs, and later we get to the big stuff. Let us begin at the beginning.

The smallest unit of structure is the note. A small number of notes may be grouped together as a motive (or motif), a collection of rhythmic, melodic, and/or harmonic materials that serves as the seed that will generate the material of the rest of the piece. A good example is the G-G-G-E@ motive at the beginning of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5. All of the materials of this first movement are derived from these four notes. This is what we call developmental music because, like a fertilized egg, everything grows from this single idea. The motive is the equivalent of a word in written language.

The next largest structural unit is the phrase. It is the equivalent of a sentence and concludes with a sense of repose we call a cadence. Cadences may be conclusive or inconclusive depending on where they are in the piece. Everything we do in music is related to phrases; their composition, analysis, and performance. Phrases may be joined in a pairing we call a period. Generally, a period consists of an antecedent phrase that makes a musical statement and is followed by a consequent phrase that responds to it. Two related periods may be joined together to form a double period, the equivalent of a four-line stanza in poetry. In fact, there is much about the structure of music that reminds us of poetry and vice versa. Tonal compositions may have as few as four phrases and larger pieces, such as the movement of a symphony or sonata, may have as many as the composer desires.

In larger structures like these the next structural division is called a section that may comprise any number of periods, double periods, or unattached phrases. If it cadences on the tonic it is called a closed section and if it ends with a half cadence or in a key other than the tonic it is considered an open section. A piece may have any number of sections. If it comprises two sections it is in binary form (A-A1). The most common ternary form (three sections) has an A-B-A1 structure. There is no limit to the number of sections that a composer may employ. When diagramming structure we use lowercase letters for phrases and uppercase for sections. A section is the equivalent of a paragraph.

Larger pieces, such as sonatas, symphonies, and concertos usually have several movements that are equivalent to chapters. A movement is a separate piece of music that may or may not be thematically related to the other movements. In a cyclical piece thematic elements from the first movement reappear in succeeding movements. Movements are often in related keys.

Multi-sectional Instrumental Forms

The structure of large musical forms is not dissimilar from that of large literary works. A novel comprises chapters, paragraphs, sentences, phrases, words, and letters. In music we have movements, sections, periods, phrases, and notes. The following discussion relates to the most common forms employed by the composers of the common practice period. Many of these forms are still in use today. They may range in size from sixteen measures to six hundred. What is significant about the proportion is the amount of time the composer has allotted for the statement, restatement, and development of ideas. Some works may be considered expository because they present lovely melodies and harmonies but little is done to develop these materials. At the other end of the spectrum are purely developmental works that may begin with seemingly inconsequential ideas but, as time goes by, these ideas grow and develop in extraordinary ways. On larger canvases we get to see these ideas go through a variety of transformations much like what happens to the protagonist in a great drama. At the end of the play that character has been transformed in some significant way that has moved and transformed the audience as well.

Binary form

Binary form

Tonal composers have employed a wide variety of musical forms over the past four hundred years. The simplest of these is known as binary form because it contains two sections. There are equal binary forms where both halves are the same length and unequal ones in which the second part is longer than the first. The dance music of the Baroque Period is a rich source of binary forms whose A sections usually ranged from eight to twenty-four measures depending on the tempo of the piece. If the composition is in major the A section may end with a cadence on V or in the key of the dominant. If it is in minor the modulation is to the relative major. Almost without fail, there is a repeat sign and the section is played again. The second part (A1) uses melodic material very similar to the first in a more adventurous harmonic framework and ends with an authentic cadence in the tonic. This section is also repeated. A form known as rounded binary is notable because the second part features a return to the opening material in the original key (||: A :||: A1 A :||).

Ternary form

Ternary form

Perhaps the most important ternary form of the 18th century was the minuet & trio that was essentially an A-B-A1 arrangement. A binary form minuet (A) was paired with a second, simpler minuet (B) that provided just a touch of thematic contrast in a related key. At the end of the second minuet, referred to as the trio because the texture often thinned to three musical lines, there is the indication “da capo” (to the head) that tells the musicians to return to the first minuet that they play without the repeats. In the Romantic period, beginning with Beethoven, this form got continually faster and more complex evolving into what we now think of as a true scherzo. In the early 18th century the term was applied to lighter works in 2/4 time. With Haydn it became a tempo designation and later it became a replacement for the minuet. In the 19th century the same form was often used for its most popular dance, the waltz.

Rondo form

Rondo form

There are a number of different rondo forms. What they all have in common is that they begin and end with an A section. Where they differ is the number and nature of the sections that alternate with restatements or variations of A. The simplest rondo has an ABACA structure and this may be extended to A-B-A-C-A-D-A. The arch, or bow, rondo form has the symmetrical structure of A-B-A-C-A-B-A. Occasionally, in more complex rondos where the A section may be rather long, the form was truncated by the removal of the A after the C resulting in an A-B-A-C-B-A structure. In listening to, or analyzing, rondos it is interesting to see in what condition the A section returns and how closely the alternating sections are related to each other, if at all. The alternating sections are very often in related keys and occasionally a restatement of A may be in the opposite mode or it may be modified by change of register, dynamics, or instrumentation. This form was often used for the final movements in sonatas and symphonies.

Sonata form

Sonata form

Sonata form, or sonata-allegro form, is the most frequently used complex form in the instrumental music of the Classic/Romantic Period. Almost every first movement of untold numbers of sonatas, symphonies, concertos, and string quartets employed this form that has a long history of evolutionary process. It has also been used for second and fourth movements as well. If there is a third movement it is usually in ternary form (minuet & trio). Sonata form is more of a design concept than a prescribed structure. Its flexibility has given rise to myriad variants. A huge number of books and articles have been written about this subject. The following discussion will give you a general sense of the problem and your further investigations of particular examples will teach you about the details. Basically, the form is a large rounded binary comprising an exposition that may be repeated, a development section that is followed by a recapitulation.

The exposition contains two contrasting groups of materials. Group I is presented in the tonic and is traditionally more vigorous than Group II. It is followed by a transition that modulates to the key of the second, more lyrical, group, which is either the dominant or the relative major if the piece is in minor. The exposition ends with a closing group that usually reprises motives from group I and sounds very cadential with an insistence on the establish-ment of the new key. There is often a repeat sign at the end of the exposition. In the 19th century, as symphonic movements got larger and more complex, the repeat was dropped from common practice and, eventually, from scores. Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 (1824) was his first in which the repeat is absent.

The development section is essentially a fantasia on material from the exposition. There is no way of knowing in advance what material will be developed, and sometimes it is only a minor detail, not the prominent theme. It is the most harmonically unsettled section and features only tonicizations. There are no cadences here because the development is supposed to be a turbulent mix of melodic, rhythmic, and harmonic excitement and instability, all of which lead to the climax. As the storm subsides the harmony stabilizes on a long dominant pedal that prepares us for the return to the beginning back in the tonic.

The recapitulation is a modified restatement of the exposition. Traditionally, it connects group I and group II with a transition that pretends to modulate but returns to the tonic. Thus, all three groups (including the closing group) are in the home key. This section can be the most intriguing for the analyst because the modifications to the exposition may be very subtle. Very often, the listener is not aware that something has been added or deleted, or reorchestrated, or shifted to another octave, or had its harmony altered. While the development section is just that–the obvious juggling of primary motives––the “recap” is the place of compositional magic where the composer practices a “sleight of ear,” leading us to believe that this is a da capo repeat, which it is not.

Frequently, the momentum at the end of the recapitulation is too great to allow the composer to conclude there so a coda is added. This section was originally quite brief and practiced a kind of deception. Its use of primary materials leads us to believe that this will be a second exposition but turns out to be an abbreviated version of group I and brings the piece to a complete stop. Codas were never the same after Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 in which the coda of the first movement, which turns out to be another development section, is larger than the exposition and is followed by its own codetta (little coda).

Sonata-rondo form

Sonata-rondo form

There is a hybrid form known as sonata-rondo that combines aspects of both its namesakes. It typically follows an A-B-A-C-A-B1-A plan in which the first A and B are analogous to groups I and II in sonata form. The second A is the equivalent of the closing group while the C section is a development. The final A, B1, and A serve as a kind of recapitulation and are entirely in the tonic. Like the forms from which this derives it may have many variants. Individual pieces may be judged to be somewhere on a scale that runs from sonata to rondo. The major difference between them is that in sonata-rondo the exposition (A-B-A) is not repeated as in most sonata forms. This form was often used for symphonic finales.

Theme and variations

Theme and variations

The concept behind theme and variations is quite simple although nothing is simple when it comes to the creativity of great composers. The form begins with the theme, often in simple binary form, followed by a series of variations that may, or may not, be the same length as the theme. At the end there may be a reprise of the theme or not. There is no prescribed number of variations that may be employed. There may be as few as three or as many as thirty-two. This form gives the composer the opportunity to apply extreme inventiveness to a single musical idea. The character of the variations may cover a wide spectrum of emotional states from slow and contemplative to ecstatic virtuosity. The basic jazz form of head-solos-head is a descendent of this practice. A composition that employs the theme and variations structure could stand alone or be part of a larger multi-movement work.

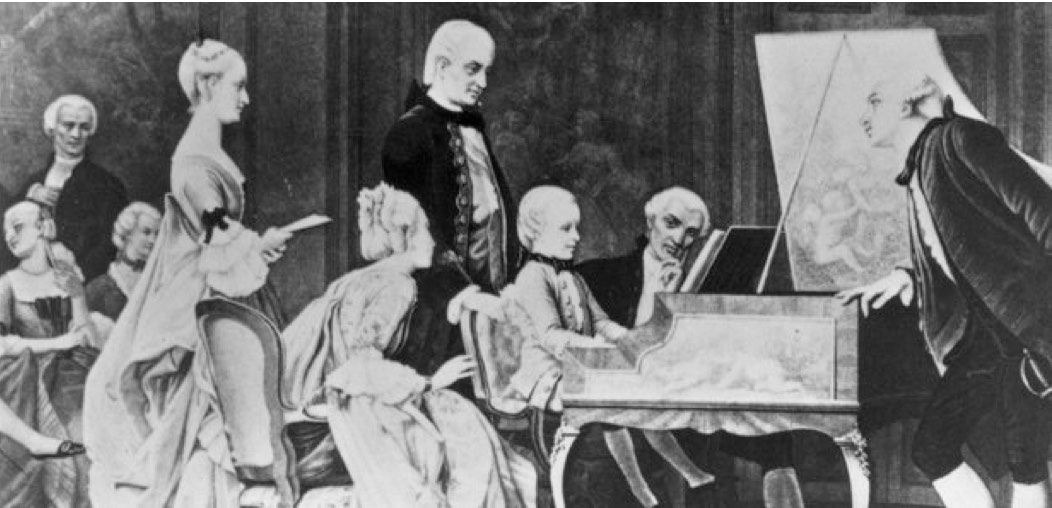

In this form, the theme does not have to be original. Countless composers have taken someone else’s theme, or a folk song, and played around with it, as did Haydn in the second movement of his “Surprise” Symphony. The operative concept in the execution of this form and, indeed, all musical activities is the word “play.” We play the piano or we play around with musical ideas. The playfulness that is so much a part of childhood is, thankfully, still alive and well in the spirits of adult composers and performers. The perfect depiction of this playfulness occurs in the film Amadeus in the scene where Mozart listens to the uninspired little piece that Salieri wrote for the Emperor to perform and then proceeds to sit at the piano and transform the dull ditty into a delightful bonbon.