Notes

Harmonizing with Triads

The construction of triads

An interval consists of two notes played simultaneously or consecutively. A chord is a discrete collection of three or more notes that function as a harmonic unit. Its constituents may be played simultaneously or consecutively. Most of the time we see or hear all the notes of a chord in close proximity to each other, but other times we are presented with incomplete harmonic information. In other words, composers do not always use all the notes all the time.

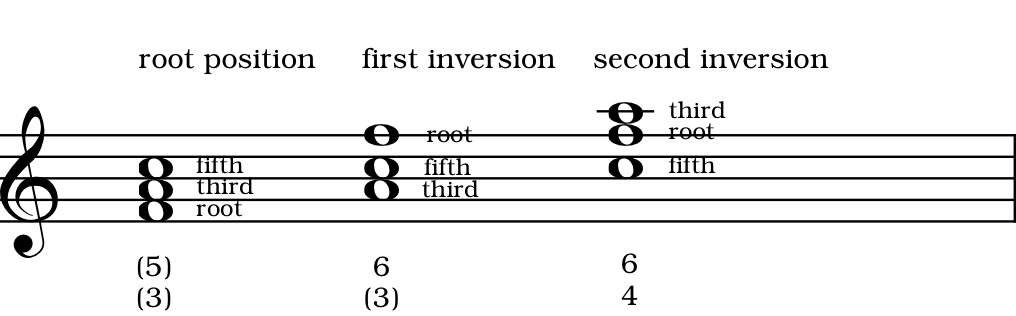

The basic harmonic unit in tonal music is the triad, a three-note chord built of 3rds. Harmony based on 3rds is labeled tertian (i.e., every other note in scalar motion). The note on which the chord is built is called the root; another note is added a 3rd above the root and is called the third; the other member of the chord lays a 5th above the root (and a 3rd above the third) and is called the fifth (see Example 5-1, root position). In every triad there are three intervallic relationships: between the bottom note and the middle note, between the bottom note and the top note, and between the middle note and the top note. Each of these intervals contributes to the way your brain processes the aural data it receives, but the intervals measured from the bottom are the most critical because the lowest sounding note is the harmonic foundation.

A triad may appear with any of its three notes in the lowest position we call “the bass.” We use this appellation even though it may not actually be in the bass voice or bass clef. When the root is lowest, the triad is most stable and is said to be in root position. As such we have 3rds between each of the notes and a 5th between the root and the top note. It is important to remember that the root is not always the same as the bass (the lowest sounding note). The root and bass are the same only in root position.

If we rearrange the triad, making the third the lowest note and the root the top note, the triad is in first inversion. In this position there is a 3rd between the bass and the middle note, a 6th between the bass and the root, and a 4th between the middle note and the root. This is a different collection of intervals than that found in root position. They both have the same root but provide the listener with two different aural experiences. In this inversion the triad is somewhat less stable than it was in root position.

When the fifth is lowest, the triad is in second inversion. The special sound of the second inversion results from the 4th between the bass and the root, the 6th between the bass and the third, and the 3rd between the root and the third. Later, we will see that the fourth between the bass and the root creates a sonority that is quite unstable and must be handled with care.

Example 5-1. Inversions of Triads

In Example 5-1, the intervals above the bass are indicated for each position of the triad. This practice is known as figured bass in which the Arabic numerals serve as a convenient shorthand label for each form. This system, also known as thoroughbass, was essential to the instrumental chamber music of the Baroque Period during which the harpsichord player, as accompanist, often had the bass line and Arabic numerals and was expected to improvise the rest of the texture based on the information provided. In their most common form triads are abbreviated as follows:

(root position) is assumed and is not notated;

(first inversion) is abbreviated as 6;

(second inversion) is notated as 6/4.

Triads in other arrangements

The triad is not always presented with all of the notes within an octave, called close position, as in Example 5-1 above. Sometimes chords appear in open position, with the notes farther apart (more than an octave). Triads must always be made from letter combinations of root, 3rd, and 5th regardless of the accidentals used. For example, a C minor triad is comprised of the notes C, E@, and G, never C, D#, and G. Only the following combinations are possible (practice reciting these combinations to assure accuracy):

A-C-E B-D-F C-E-G D-F-A E-G-B F-A-C G-B-D

Therefore, whenever you see a chord that is in open position, or jumbled up, all you need to do is match what you see to the seven combinations above.

Here is an interesting question: How many C triads are there on the piano keyboard? In other words, how many combinations of C, E, and G are there?

The answer is 392. There are eight Cs, seven Es, and seven Gs. 8 x 7 x 7=392. Wow!

The four types of triads

There are four types (qualities) of triads whose names depend on the interval between the root and 3rd and interval between the root and 5th:

Table 5-1. How Triads Are Labeled

When the 3rd is And the 5th is The quality is

minor diminished diminished

minor perfect minor

major perfect major

major augmented augmented

In Example 5-2 we see the four types of triads built on the root G. Only major and minor triads may be used as tonics. The diminished triad only appears as iio, vio, and viio while the augmented triad is occasionally used as an altered form of the dominant.

Example 5-2. Types of Triads

Using chord symbols to name triads

Every triad has two names––the name of the root and the name of the quality. Thus, a major triad with a root of G is named “G major” and is notated by the capital letter G. For major triads it is not necessary to indicate the quality in the label––if we see just the letter G we will know it refers to G major. A minor triad with a root of G is named “G minor” and is notated as Gm. Use “+” for augmented (or “aug”) and “o” for diminished (or “dim”). Do not use the archaic system that assigns a plus (+) to major and a minus (-) to minor. The minuses that students write on their homework and test papers tend to get too small to read clearly and the negative appellation is an inappropriate value judgment.

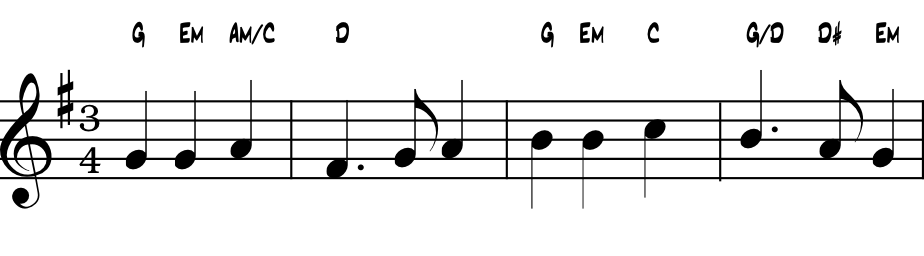

Chord inversions can be notated by adding the bass pitch after a slash. For example, Am/C indicates an A minor triad with C in the bass (first inversion). This use of chord symbols is called lead sheet notation and is common in popular sheet music and jazz scores and is always written above the chord (Example 5-3). The simplest lead sheet scores do not contain information about inversions, but you would do well to use the slashes when appropriate because the bass line is so important in tonal music.

Example 5-3. America (opening)

Numbering the triads

We use Roman numerals to identify the scale step on which the triad is built and Arabic numerals to indicate the inversion. In this text the Roman numerals will appear in uppercase to represent major and augmented triads and in lowercase for minor and diminished. Thus, a C major chord in first inversion (with E in the bass) in the key of C major is labeled I6. The Roman numeral “I” indicates that the root of the triad (C) is the first note (tonic) of the key (C major). The Arabic numeral “6” indicates that the triad is in first inversion—that there is a 6th between the bass and the root.

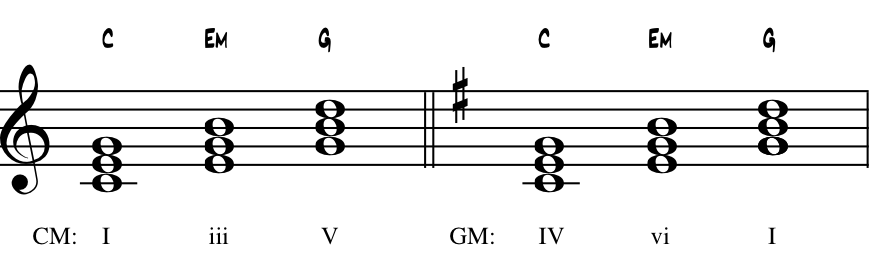

Note that the lead sheet name is the same no matter what key the triad is in. (Cm is the label for C-E@-G whether it is the tonic in C minor, the submediant in E@ major, or the subdominant in G minor. Note, also, that the same scale degree indicates a different triad in different keys (e.g., a I chord in CM is a C major triad, but a I chord in FM is an F major triad). In Example 5-4 we see that the same three triads are labeled differently according to the key in which they are found.

Example 5-4. Examples of Chord Labels

It is essential to know both systems of notation thoroughly and to be able to translate from one system to the other rapidly. Whereas lead sheet notation treats all chords as isolated units without regard to key, the numbered scale step notation relates the chords to one another and also indicates their functions within the tonal system of a particular key.

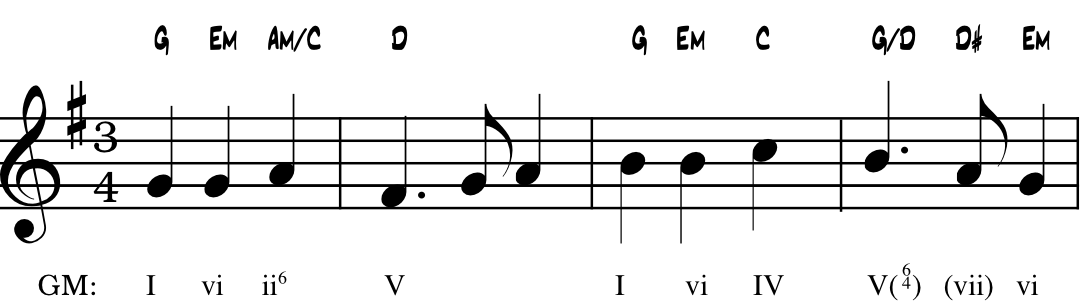

To translate lead sheet notation into scale step notation, use a Roman numeral for the scale step of the root of the triad. Indicate the quality of the chord by the use of upper or lowercase. Then, add figured bass notation where necessary to show inversions. For example, the first chord in Example 5-5 is G major. In the key of GM a G major triad is I. The second chord, Em, is vi in GM. The third chord is Am/C, the supertonic in the first inversion (ii6).

Example 5-5. America (opening)

The quality of triads in major keys

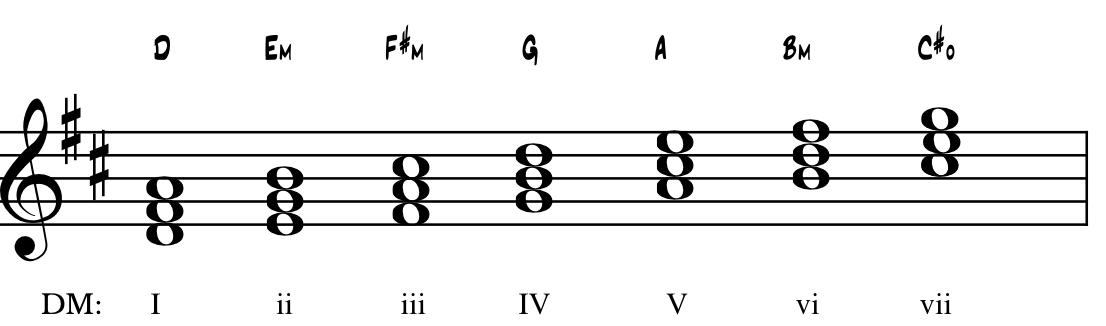

As may be seen in Example 5-7, major keys contain three major triads (I, IV, and V), three minor triads (ii, iii, and vi), and one diminished (vii). This distribution results in a hierarchy of importance. The major chords are the primary triads, the three triads you would learn if you could only learn three chords. There are four secondary chords and the unique one is vii, the only one of this family of chords that is diminished.

Example 5-7. Triad Qualities in Major

The quality of triads in minor keys

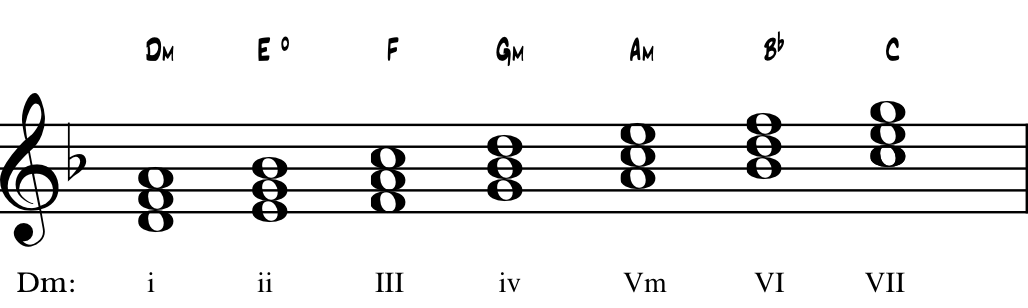

The family of chords in minor is larger than in major due to the three forms of the minor scale. By comparing the triads in natural minor (Example 5-8) with those in major (Example 5-7) you will notice that in minor the tonic, subdominant, and dominant chords are all minor––the opposite of their qualities in major. Also, now it is the supertonic that is diminished, not the leading tone (which is replaced by the major subtonic). The mediant and submediant, which were minor, are now major. In many ways, major and minor chord collections seem to present two polarities.

Example 5-8. Triad Qualities in Natural Minor

The natural minor scale, formerly known as the Aeolian mode, contains a seventh tone that is a whole step below the tonic. Therefore, dominant harmonies built on that scale do not contain a leading tone and create an archaic “modal” sound, rather than a “tonal” one, when moving to the tonic. The problem of weak dominants is fixed by the addition of the leading tone to V and vii and the result is known as harmonic minor. In a sense, harmonic minor borrows the V and vii chords from major (Example 5-9).

Example 5-9. Triad Qualities in Harmonic Minor