Notes

Modern Music:

A Personal Viewpoint

Stephen Jablonsky

Many years ago I went to a modern music festival that Pierre Boulez conducted with the London Philharmonic. Over the course of three evenings he played many of the orchestral masterpieces of the first half of the 20th century. Each piece was beautifully performed and intriguing to hear, but something amazing happened when he played the final piece—Stravinsky’s Petrushka. During the performance I realized how dark and angry all the other pieces were in comparison to the brightness and glitter of Petrushka's bristling sonorities. A great deal of the neurosis and madness of the 20th century found its way into its music, and the expressionists were, probably, the worst of the bunch. If you look at Schoenberg’s paintings you will have a better idea why much of his music sounds the way it does. He needed more time on Freud’s couch.

I love Debussy’s music because his structures are as exquisitely complicated as the other moderns but his stuff is beautiful from beginning to end. Ravel deliberately put a modicum of dissonance into his music but even that spice is sweet. Some modern music, especially pieces written in the second half of the 20th century, went off track when it got so obtuse that the audience could not remember three notes when they left the theater. Many of the moderns forgot that music is about drama, not serial calculations and note sequencing. To be modern is not, in and of itself, a virtue. Modern does not have to be difficult, or even offensive. Melody is not a bad thing every once and a while. There is something very pleasurable about singing along with every note in Prokofiev’s music. People do like to sing along whether at camp or at Carnegie. OK, maybe they do not have to sing the whole thing, but they have to hum something on the way home from the concert.

Modern jazz has suffered the same fate as classical music. When it abandoned the idea of being danceable or tuneful it lost its audience and its revenue. Picture a ballroom filled with hundreds of people jiving to the Count Basie band. Then, picture a small jazz club on 52nd Street or in the Village where a handful of avid listener’s are wondering when, and if, the tune will ever come back. The musicians are digging the improvisations but the audience has been disconnected from the primal essence of music. They are dazzled by the intellect and the technique but are befuddled and lost much of the time. Some music provides intellectual joy while other music attends to important emotional needs. Great music does both.

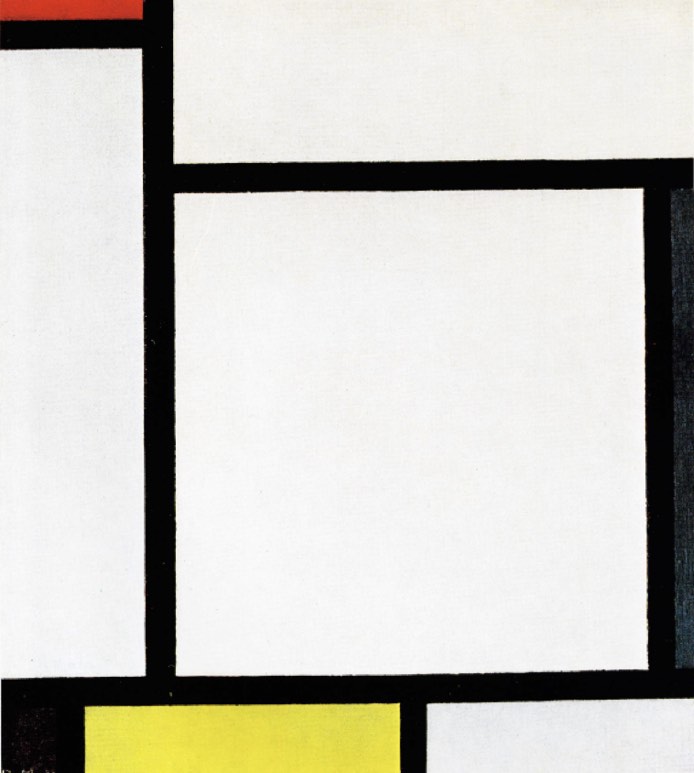

Sometimes the theory of modern compositional practice got in the way of the music. Think about the intriguing, influential philosophies of Cage in comparison to his often insipid music. In much of his music he gave up control of the compositional process, and this is problematic because it is the sonic evidence of a brilliant mind at work that delights and fascinates us. Webern's late stuff is as devoid of emotion as the late experiments of Mondrian--fascinating but cold, made for the head, not the heart. The application of abstraction in art and music is a process where the details are distilled away and only the essence is left. In Webern what you are left with is a few well-chosen tones in a relatively thin texture. The audience is expected to savor each pitch but may arrive at the end of the experience still feeling hungry. Anton’s later music often reminds me of a meal of hors d’oeuvres. On the way home I feel like stopping for a Whopper.

So, what is at the heart of the problem? If the audience cannot follow the musical narrative that is being told then it is all just a lot of smoke and mirrors, or worse--musical blah-blah. Music must first be engaging and entertaining, and then it can be art. It needs to be magical. It is already mysterious. Most of all, there must be a significant and palpable connection between the humanity of the composer and the hearts and minds of the audience.

Piet Mondrian 1921