Chapter 9:

Hear the Magic: Audio Design for Immersive Storytelling

Introduction

Audio design is an essential component of theatrical production, responsible for crafting the auditory landscape that enhances storytelling, sets emotional tone, and supports performers. In recent years, many professionals and educational texts have moved toward using the term "audio design" to clarify the discipline’s dual focus: sound (ambient effects, environmental sounds, voice reinforcement) and music (original composition, underscore, playback cues). This chapter explores the history of audio design, fundamental principles of sound engineering, equipment used in theatrical audio, running a soundboard, the physics of sound, techniques for balancing audio in live performance, networking for sound systems, creating immersive soundscapes, and using audio to enrich narrative and emotional impact.

Oral Traditions to Soundscapes

Sound has been a fundamental part of storytelling since the earliest human civilizations. Oral traditions relied on the power of voice, rhythm, and musical elements to pass down myths, histories, and cultural narratives. Around fires, Indigenous communities across the world used drumming, chanting, and natural sound cues to enhance their stories, evoking emotions and creating immersive auditory experiences.

As theatre evolved in ancient Greece and Rome, sound played a crucial role in amplifying the human voice in large amphitheaters. Architects designed these spaces with natural acoustics in mind, ensuring that actors’ voices carried throughout massive audiences. The introduction of mechanical sound effects, such as thunder sheets and wind machines, became common in the Renaissance period, bringing a new level of realism to theatrical storytelling.

The Industrial Revolution brought advancements in sound technology, including the invention of the phonograph by Thomas Edison in 1877, allowing for the recording and playback of sound. The early 20th century saw the introduction of microphones and electronic amplification, transforming theatre sound. The first documented use of amplified sound in theatre was in 1921 when Lee De Forest, the inventor of the Audion vacuum tube, experimented with amplified voice projection.

By the mid-20th century, magnetic tape recording and playback allowed for more complex soundscapes, with designers integrating pre-recorded effects, music, and ambient noise into productions. The rise of Broadway and West End productions in the 1950s and 1960s saw increasing use of multi-channel sound systems, enabling designers to shape the audience’s auditory experience with greater precision.

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, digital technology revolutionized theatre sound design. The development of digital audio workstations (DAWs) such as Pro Tools and Ableton Live allowed for precise sound cue programming and playback. Wireless microphone systems, digital mixing consoles, and networked audio solutions like Dante and AVB further enhanced control over live sound.

Today, immersive sound design is pushing the boundaries of theatrical audio. Techniques such as 3D audio, binaural recording, and ambisonic soundscapes create deeply immersive environments for audiences. Sound baths, which use carefully designed soundscapes for therapeutic and experiential purposes, have also influenced modern theatre, demonstrating how sound can engage audiences on a sensory level beyond traditional amplification.

From ancient oral storytelling to state-of-the-art digital mixing, sound design continues to evolve, enhancing the way stories are told on stage. The integration of artificial intelligence and spatial audio promises an even more dynamic future for theatre sound, ensuring that the auditory experience remains as compelling as the visual spectacle.

Notable Sound Designers and Engineers

Throughout history, several sound designers and engineers have shaped the evolution of theatrical and cinematic sound. Their contributions have advanced the field and set new standards for immersive audio storytelling.

Abe Jacob

Known as the "Father of Theatrical Sound Design," Abe Jacob pioneered modern theatrical sound reinforcement on Broadway. His work on productions such as Jesus Christ Superstar and A Chorus Line set new benchmarks for sound clarity and system design in live theatre.

Jonathan Deans

A prominent sound designer in musical theatre, Jonathan Deans has worked on productions including Ragtime , The Lion King , and Cirque du Soleil shows. His innovative use of surround sound and immersive audio environments has influenced theatrical sound design worldwide.

Autograph Sound

Founded by Andrew Bruce, Autograph Sound has been a leading force in West End theatre sound design, providing high-quality systems for numerous productions, including Les Misérables and The Phantom of the Opera .

Ben Burtt

In film sound design, Ben Burtt is a legendary figure known for creating iconic soundscapes in Star Wars , Indiana Jones , and Wall-E . His pioneering use of synthesized and organic sounds has influenced sound designers in both film and theatre.

Gary Rydstrom

A multi-Academy Award-winning sound designer, Gary Rydstrom has worked on Pixar films such as Toy Story and Finding Nemo . His expertise in creating rich, layered soundscapes has influenced live and digital sound storytelling.

Nevin Steinberg

A modern Broadway sound designer, Nevin Steinberg has worked on hit productions like Hamilton and Hadestown , utilizing digital mixing and reinforcement techniques to balance sound clarity with artistic intent.

These designers and engineers have shaped the evolution of sound in theatre and film, demonstrating the importance of audio as a storytelling tool.

Sound Engineering and Equipment

Sound engineers in theatre are responsible for managing audio elements, ensuring clarity and consistency. Essential equipment includes:

Types of Microphones

- Dynamic Microphones : Durable and resistant to moisture, these microphones are commonly used for live vocals and instruments. They do not require external power and are ideal for high-volume sound sources.

- Condenser Microphones : More sensitive than dynamic microphones, condenser microphones capture detailed and high-fidelity sound. They require an external power source (such as a battery or phantom power from the audio console) and are often used for theatrical ambiance, orchestras, and high-quality vocal recordings

Lavalier (lapel) microphones

– Small, wearable microphones ideal for individual performers.

Handheld microphones – Used for singers, presenters, or interactive performances.

Shotgun microphones

– Directional mics used to capture sound from a distance.

Boundary microphones – Placed on the stage to pick up ambient and group sounds.

Parts of A Microphone

Microphones are essential tools in sound design, converting sound waves into electrical signals. The main components of a microphone include:

Diaphragm: A thin membrane that vibrates when struck by sound waves, initiating the conversion of acoustic energy into electrical signals.

Coil (Dynamic Microphones): In dynamic microphones, the diaphragm is attached to a coil of wire that moves within a magnetic field, generating an electrical signal.

Condenser Element (Condenser Microphones): Condenser microphones use a diaphragm placed near a charged backplate, requiring phantom power to operate.

Magnet: Provides the magnetic field needed for the coil to generate an electrical signal in dynamic microphones.

Preamp Circuit: Amplifies the weak electrical signal before it reaches the mixing console.

Housing: The external casing that protects the internal components and influences the microphone's durability and acoustic properties.

Mixing Consoles

An audio mixing console, or soundboard, controls input levels, equalization, and effects for multiple audio sources. Digital consoles offer advanced routing and programming features, while analog consoles provide hands-on control with physical knobs and faders.

Using the Behringer X32 Sound Board

The Behringer X32 is a popular digital mixing console in theatre sound design. To use it effectively:

- Power On – Ensure the board and connected devices are properly powered.

- Routing Inputs and Outputs – Assign microphones and playback devices to specific channels.

- Setting Gain and EQ – Adjust input gain and use the equalization settings to enhance clarity.

- Creating Mixes – Use faders to balance sound and create monitor mixes for performers.

- Applying Effects – Utilize built-in reverb, delay, and compression settings.

- Saving and Recalling Scenes – Store mix settings for consistent performance execution.

Speakers and Amplifiers

Speakers project sound to the audience, and their placement is crucial for even coverage. Amplifiers power the speakers, ensuring sufficient volume and clarity.

Signal Processors

Devices such as equalizers, compressors, and reverbs modify sound signals for optimal performance.

Cables

Proper audio connections are essential for a reliable sound system. Various types of cables are used in theatre sound:

- XLR Cables : Balanced cables used for microphones and professional audio equipment, reducing signal noise over long distances.

- TRS (Tip-Ring-Sleeve) Cables : Balanced cables used for line-level signals, often found in instruments and headphones.

- TS (Tip-Sleeve) Cables : Unbalanced cables used for guitars and other instruments, prone to signal interference over long distances.

- RCA Cables : Common in consumer audio equipment, used for connecting playback devices like CD players and turntables.

- Ethernet (Cat5e/Cat6) Cables : Used for digital audio networking, such as Dante and AVB systems, allowing multiple channels of audio to travel over a single cable.

Playback Systems

Cue-based software (e.g., QLab, Ableton Live) allows sound designers to trigger sound effects and music at precise moments.

Using QLab

QLab is a powerful and common software tool for cueing and playing back sound in live theatre productions. It allows designers to control multiple sound cues with precision. Here’s how to use QLab for a show:

Step 1: Setting Up a Workspace

- Open QLab and create a new workspace.

- Configure audio output settings, assigning outputs to speakers or Dante devices.

Step 2: Creating Sound Cues

- Click the “+” button to add a new sound cue.

- Drag an audio file into the cue list.

- Set the start and stop times for the cue as needed.

Step 3: Editing Sound Cues

- Adjust volume and fade-in/fade-out times.

- Set loop points if a sound effect needs to repeat.

- Use cue sequencing to trigger sounds in a specific order.

Step 4: Running the Show

- Organize cues in order of execution.

- Assign hotkeys for quick manual triggering.

- Run through a tech rehearsal to confirm sound cues function correctly.

Setting Up a Sound System

Properly setting up a theatre sound system is crucial for achieving clear and balanced audio. The process involved multiple steps, from connecting speakers to testing microphones.

Step 1: Planning the System

Before setting up, determine the needs of the production:

- Identify how many microphones, speakers, and playback devices are needed.

- Plan speaker placement for optimal sound coverage.

- Decide on necessary signal routing and cable management.

Step 2: Connecting Speakers and Amplifiers

- Position speakers correctly – Place front-of-house (FOH) speakers facing the audience and monitor speakers for performers.

- Connect amplifiers – If using passive speakers, connect them to amplifiers using speaker cables. Active speakers have built-in amplification and require only power and signal connections.

- Run audio cables – Use balanced XLR or TRS cables to connect the mixing console to amplifiers or powered speakers.

- Test speaker output – Send a test signal to confirm proper speaker functionality and placement.

Step 3: Setting Up the Mixing Console

- Power on the console – Ensure all connected devices are turned on in the correct sequence: sources first, then console, then amplifiers.

- Assign input channels – Connect microphones, instruments, and playback devices to designated channels.

- Route outputs – Assign main outputs to speakers and auxiliary outputs to monitors as needed.

- Set gain structure – Adjust input gain levels to prevent distortion and ensure clear sound.

Step 4: Connecting and Testing Microphones

- Check wireless microphone frequencies – Ensure frequencies do not interfere with each other.

- Place microphones correctly – Position lavaliers, handheld, or instrument microphones according to the needs of the production.

- Perform a sound check – Have actors and musicians speak or play at performance volume to set levels.

- Adjust EQ and dynamics – Fine-tune equalization, compression, and effects to achieve clarity and balance.

Step 5: Running a Line Check and Sound Check

- Verify all connections – Ensure every microphone and speaker is functioning correctly.

- Test playback sources – Run sound cues through the system to check levels and clarity.

- Adjust monitor mixes – Ensure performers can hear themselves properly onstage.

- Run a full sound check – Conduct a rehearsal with the cast to finalize levels before the performance.

Networking for Sound

Modern theatre productions often use digital networking for sound, allowing multiple devices to communicate efficiently. Protocols such as Dante (Digital Audio Network Through Ethernet) and AVB (Audio Video Bridging) enable seamless routing of audio between soundboards, computers, and amplifiers over an Ethernet network. This reduces the need for extensive cabling and provides greater flexibility in sound system design.

Creating Soundscapes

A soundscape is the combination of sounds that define an environment, mood, or atmosphere in a production. To create an effective soundscape:

- Identify the scene’s needs – Consider how sound can support storytelling.

- Layer sounds effectively – Combine ambient noise, musical elements, and effects for depth.

- Use panning and spatial techniques – Position sounds to create immersion.

- Employ dynamic changes – Adjust intensity and timing for dramatic effect

Using Sound to Enhance Storytelling

Sound plays a crucial role in guiding audience emotions and reinforcing narrative elements. Techniques include:

- Character Themes – Assign specific motifs or sounds to characters.

- Emotional Underscoring – Use subtle background music to enhance mood.

- Diegetic vs. Non-Diegetic Sound – Determine whether sound is part of the world of the play or an external artistic choice.

- Silence as a Tool – Strategic use of silence can heighten dramatic tension.

The Physic of Sound

Understanding the physics of sound is fundamental to sound design. Key concepts include:

Frequency and Pitch – Frequency (measured in Hz) determines pitch; higher frequencies produce higher pitches.

Amplitude and Volume

– Amplitude determines loudness, measured in decibels (dB).

Waveform and Timbre – The shape of a sound wave influences its tonal quality.

Reverberation and Echo – Sound reflects off surfaces, creating depth and resonance.

Directional Sound – Speakers and microphones capture and emit sound in specific patterns.

Balancing Sound

A well-balanced sound mix ensures clear, immersive audio for the audience. Techniques include:

- Setting proper levels – Ensuring each sound source is audible without overpowering others.

- Equalization (EQ) – Adjusting frequency ranges to enhance clarity and prevent muddiness.

- Panning – Distributing sound between left and right channels for a natural spatial effect.

- Managing dynamics – Using compressors and limiters to smooth out volume variations.

- Room acoustics consideration – Adapting the mix based on the theatre’s acoustics to minimize feedback and reflections.

The Roles in Sound

Sound in theatre requires a team of professionals with distinct roles to ensure high-quality audio execution. These roles include:

Sound Designer

The Sound Designer is responsible for conceptualizing and creating the overall auditory experience for a production. They collaborate with the director and other designers to craft soundscapes, choose music and effects, and determine how sound enhances storytelling. They also provide technical documentation and guidance for implementation.

Audio Engineer

The Audio Engineer ensures that all technical aspects of the sound system function properly. They program digital consoles, adjust levels, and troubleshoot any technical issues. The engineer ensures consistency and fidelity in audio playback throughout the run of the show.

Audio 1 (A1)

The A1, or Production Sound Engineer, is responsible for operating the mixing console during performances. They mix live microphones, playback cues, and adjust levels in real-time. The A1 ensures that all sound elements are balanced and clear for both the performers and the audience.

Audio 2 (A2)

The A2, or Assistant Audio Engineer, works backstage to manage microphone distribution, battery changes, and troubleshooting audio issues for performers. They ensure all wireless and wired mics are functioning properly, assist with setup and teardown, and provide on-the-spot support during performances.

Sound Technician

A general Sound Technician assists with setup, maintenance, and operation of sound equipment. They may be responsible for running cables, setting up speakers, and ensuring that all components are in working order before each performance.

Conclusion

Sound design is a vital aspect of theatre production, requiring both artistic creativity and technical expertise. By understanding the history, engineering principles, and practical techniques of sound design, theatre professionals can enhance the audience's experience through compelling auditory storytelling. Modern technology, from digital mixing consoles like the Behringer X32 to networked audio solutions, allows for even greater precision and creativity in theatrical sound design.

Showcase your Learning

Assignment Objective:

Students will demonstrate their knowledge of sound design by creating your very own sound design for a play or story you have read.

Assignment Rationale:

As designers and technicians, it's important to understand how to creatively design sound.

Choose your Assignment:

Choose one of the options below to showcase your learning.

- Children’s Book: Choose your favorite children’s book, create sound effects and soundscape that will help enhance the story. Record yourself reading the story while cueing your sound effects.

- Dubbing Cartoons: Find a cartoon segment no longer than 3-minutes. Create your own sound effects and soundscape for the segment. Record a video of the segment playing while you cue your sound effects.

- Foley Sound: Using only things you find in the world and editing software create the sound effects needed for one scene of a play.

- Music: Using sound editing software, create a 1-minute track that takes the listener on a journey.

- Analysis: Find a scene from a movie, tv show, play, or musical online and create a sound cue list for it. Write about how the sound designer used sound to enhance the storytelling.

- Presentation: Create a presentation in which you discuss how sound works in theatre. What is needed to ensure the audience hears everything they are meant to hear?

- Roll the Dice! Let the fates decide.

All designs must include the following:

- Sound Cue List and/or Equipment list

- At least 5 Sound Effects Created by You

- Reflection: Why did you make the decisions you’ve made?

Key Terms

A1 (Audio 1) – The production sound engineer responsible for mixing live sound during performances, including microphones, music, and effects.

A2 (Audio 2) – The assistant audio engineer who manages backstage audio operations, such as mic placement, battery changes, and troubleshooting during a performance.

Amplitude – The height of a sound wave that determines its loudness, measured in decibels (dB).

Audio Engineer – A technical expert who programs the sound system, ensures proper signal flow, and maintains audio quality during rehearsals and performances.

Boundary Microphone – A microphone designed to be placed on a flat surface (e.g., stage floor) to pick up ambient or group sound with minimal interference.

Condenser Microphone – A sensitive microphone that captures detailed audio and requires phantom power; ideal for vocals, ambiance, or orchestral recordings.

Cue List – A sequential document that outlines all sound cues in a performance, including timing, content, and triggering instructions.

Dante – A digital audio networking protocol that transmits multiple channels of audio over standard Ethernet cables.

Directional Sound – Sound that is projected or captured in specific patterns, controlled by the design of the microphone or speaker.

Dynamic Microphone – A durable microphone type that does not require external power; commonly used for live vocals and instruments.

Equalization (EQ) – The process of adjusting specific frequency ranges to enhance sound clarity or shape tone.

Ethernet Cable (Cat5e/Cat6) – A cable used for digital audio networking, such as in Dante and AVB systems.

Frequency – The number of sound wave cycles per second, measured in Hertz (Hz), which determines pitch.

Gain – The initial amplification of an audio signal before it reaches the mixing stage.

Handheld Microphone – A portable microphone typically used by singers, hosts, or for audience interactions.

Lavalier Microphone – A small, wearable mic clipped to a performer, ideal for live dialogue and discreet amplification.

Mixing Console (Soundboard) – A device that controls audio inputs, levels, equalization, and outputs in a live or recorded sound environment.

Oral Tradition – A method of storytelling passed down through spoken word, often accompanied by music or rhythm.

Panning – Distributing sound across the stereo field (left to right) to create spatial dimension.

Phantom Power – A method of providing DC power (usually 48V) through microphone cables to operate condenser microphones.

Playback Software – Digital tools like QLab or Ableton Live used to program and execute sound cues during live performances.

Preamp (Preamplifier) – A circuit that boosts weak microphone signals to line level before processing.

QLab – A cue-based software program used to trigger audio, video, and lighting cues in live performances.

Reverberation (Reverb) – The persistence of sound after it is produced, caused by reflections from surfaces in a space.

Shotgun Microphone – A highly directional mic used to capture sound from a distance while minimizing ambient noise.

Signal Processor – A device that alters sound electronically, such as compressors, equalizers, or reverb units.

Silence – A deliberate absence of sound used as a storytelling device to create tension, focus, or contrast.

Sound Designer – The creative professional responsible for conceptualizing and implementing the auditory environment of a production.

Soundscape – A layered composition of sound elements (e.g., ambient noise, effects, music) used to define mood or setting in a scene.

Spatial Audio – Techniques that give sound a sense of 3D space, often using panning, delay, or multi-speaker configurations.

Speaker – A device that converts electrical audio signals into sound waves for the audience to hear.

TS/TRS Cables – Tip-Sleeve (unbalanced) and Tip-Ring-Sleeve (balanced) audio cables used for instrument and line-level connections.

Waveform – The visual representation of a sound wave’s shape, which affects its tonal quality or timbre.

Wireless Microphone System – A microphone system that transmits audio signals wirelessly, commonly used for actor mobility on stage.

XLR Cable – A professional-grade, balanced audio cable used to connect microphones and other equipment with minimal noise interference.

Video Resources

-

Designing Sound for Theatre

– Sound Designer & Composer Alma Kelliher discusses her creative process, her work on The Elephantom and why sound should be arranged like a musical score.

- How the Sound Effects In ‘A Quiet Place’ Were Made – A deep dive into foley sound as a tool for stage and screen.

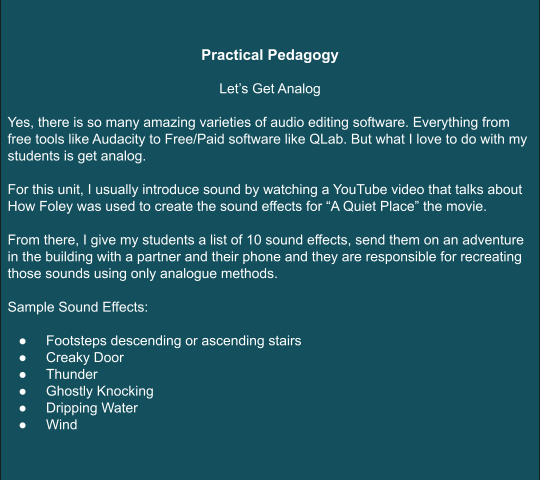

Practical Pedagogy

References

Barron, D. (2013). Sound design for the stage: Theory and practice . Crowood Press.

Eargle, J. (2012). The microphone book: From mono to stereo to surround - a guide to microphone design and application (3rd ed.). Focal Press.

Figure 53: Screenshot of QLab software interface. Adapted from QLab 4 Documentation (2021).

Hurbis-Cherrier, M. (2018). Voice & vision: A creative approach to narrative filmmaking (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Kaye, D., & Lebrecht, J. (2015). Sound and music for the theatre: The art & technique of design (4th ed.). Focal Press.

Rossing, T. D. (2014). The science of sound (3rd ed.). Pearson.

Thompson, R. (2019). Mastering sound design for theatre: A practical guide . Routledge.