Navigating the James A. Emanuel Project

The James A. Emanuel Project presents a multidimensional account of Emanuel's life, work, and influence. The project offers different points of entry into Emanuel’s writings and network that center the James A. Emanuel papers, (1922 – 2018) at the Library of Congress. The project provides the public with material, critical insights, and context for a more holistic understanding of Emanuel’s scholarly and artistic impact.

The section “James A. Emanuel: A Brief Bio” reflects the intention for the project as a whole to serve as a type of critical biography. This section traces the arc of Emanuel’s professional life with special attention paid to his publishing history. It opens with one of his earliest publications in The Omaha Bee newspaper and concludes with a quote from his last book The Force and the Reckoning.

The “Mini Stories” highlight distinct aspects of Emanuel's career as recounted by those who knew him personally. Each story focuses on his life after settling in France and contributes to the critical conversation by connecting his poetic innovations to the individuals who shaped and shared his work in the 1990s and early 2000s. These stories offer insight into this period by highlighting his collaborations with engraver and collaborator Godelieve Simons; musician Noah Howard; writer and study abroad director Janet Hulstrand; and literary critic Dan Schneider. Each story begins with archival context and culminates in a video-recorded oral history interview.

Among the project’s interpretive materials are two extended poetry analyses: one devoted to Emanuel's Black cultural poetics and another to his “Christmas Notes (1991 to 2006)”—annual summaries he shared with friends and family to track his literary and personal milestones—to offer deeper insight into his literary production and intellectual activities. Each page of the analyses is designed to be digestible on its own. The first analysis “James A. Emanuel's Black Cultural Poetics in Four Poems” uses Christel N. Temple’s Black cultural poetics to highlight Emanuel’s tradition of resistance, ancestor acknowledgement, and cultural preservation. The second analysis “James A. Emanuel's Christmas Card Padding (1991 - 2006): A Data Story” applies Kenton Rambsy and Peace Ossom Williamson’s F.L.O.A.T. (Formulate, Locate, Organize, Analyze, and Tell) method to an examination of Emanuel’s “Christmas Notes” to reveal patterns in his productivity.

The “Poetry Readings” section invites users to listen to selected works from Emanuel’s collection read out loud to experience how literary devices emerge in personal reading practices. These performances demonstrate how reading is an interpretation as each reader stresses, skips over, pauses, and emphasizes language differently (Hilscher and Cupchik 52).

The short-documentary James A. Emanuel: A Poet in Self-Exile explores the interconnection of Emanuel's personal life and his literary work. Using archival footage, interviews, animation, and live action, the documentary film captures the significance and arc of Emanuel’s journey. The documentary reflects insights from Emanuel’s autobiographies Snowflakes and Steel: My Life as a Poet (1981), The Force in the Field (1995), and The Force and the Reckoning (2001). It addresses his marriage to Mattie Etha Johnson, his son James Jr., and his decision to leave the United States. The title draws from Michel Fabre’s chapter in From Harlem to Paris, but the addition of “self” emphasizes Emanuel’s indignant agency in that decision.

Resource Collections

On the homepage, beneath the table of contents, are the “Resource Collections,” which form the substratum of the project. There are 268 materials in the resource collections that are archival scans from Emanuel's papers at the Library of Congress. These materials are curated, described, transcribed, and tagged across five categories. Many of these materials are embedded throughout the site as images, videos, and audio files. They are also accessible as “thumbnails in the left margin. When users hover over [the thumbnails], they will turn a shade of green, and when clicked a window will overlay the text previewing the resource or allowing you to interact with it” (“Quick Guide”). There is a thumbnail file in the left margin in the following paragraph; it contains an audio message by members of Emanuel's family.

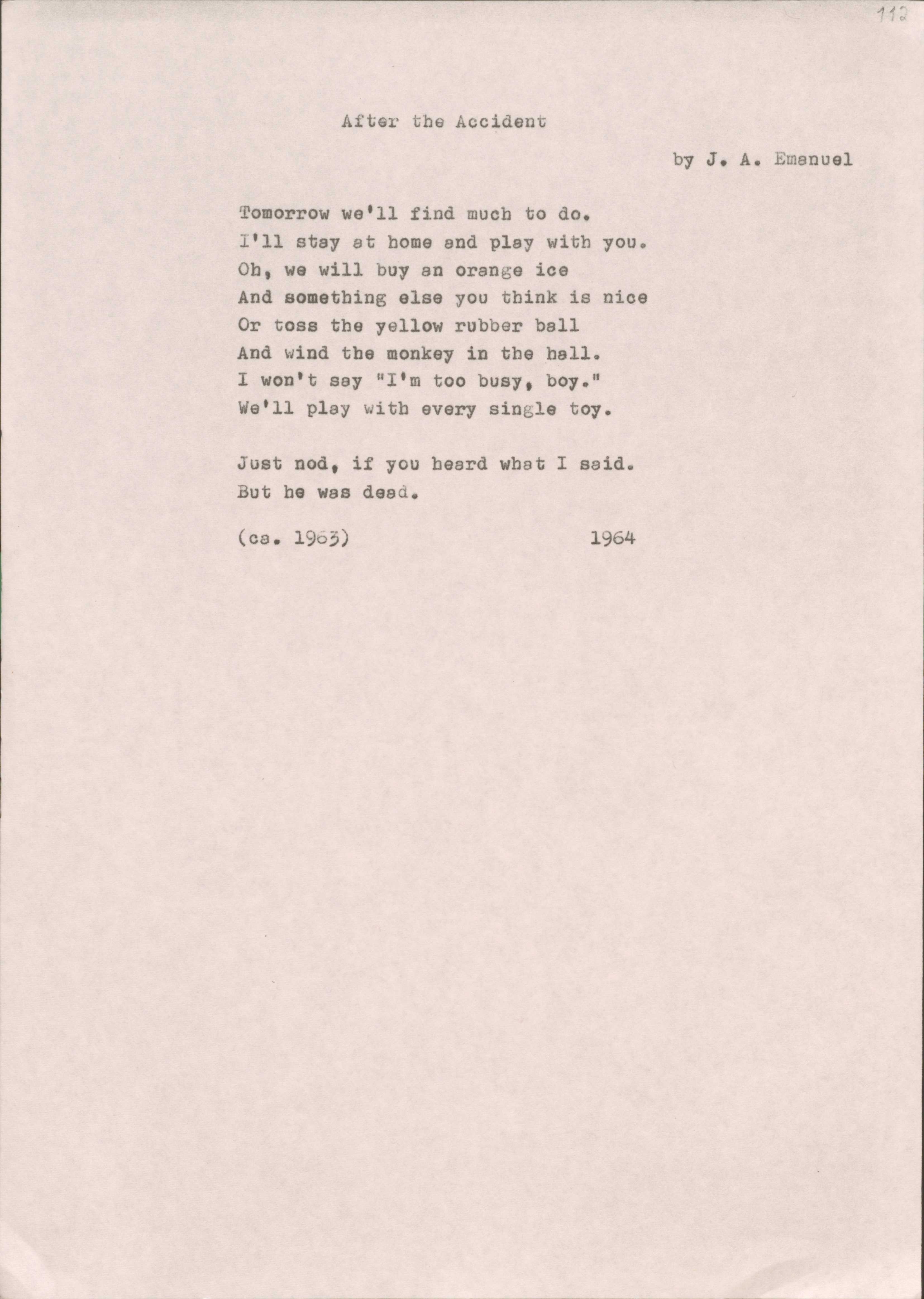

The “Poetry Collection” includes many of the poems Emanuel considered his "best of the best.” The collection also contextualizes his life, including his service in World War II, his education, his son, and his decision to expatriate to France. Some poems are rare examples of longer forms such as “El Toro” and “Between Loves: A Train from London”— both written during a stay in London. The collection also showcases Emanuel’s documentation system that he began in the 1970s, which involved including date, time, and location notations at the top of draft pages. Together, these scanned poems provide an overview of the poetic corpus held at the Library of Congress.

Figure 1. After the Accident. One of Emanuel's “best of the best” poems

The “Audio Collection” features all available audio materials from the Library of Congress. It includes rare content such as a complete interview with Langston Hughes and family messages that capture how cassette tape was a medium for maintaining contact with loved ones. The collection also includes songs, poetry readings, and the full Middle Passage album, a collaboration between Emanuel and Noah Howard. This album features what Emanuel termed his jazz-blues-and-gospel haiku. Nathalie Vincent-Arnaud, whose father performed with Emanuel in Toulouse, called this form “reste son empreinte stylistique la plus marquante.” Middle Passage includes recordings and transcriptions drawn mostly from Emanuel’s poetry collection JAZZ from the Haiku King, which constitutes a “hybridized text of words, musics, voices, and sounds” that intensifies “the global staging of African American culture through the impulse of 'jazz' music to engage diverse people all around the world in a common dialogue” (Smith 80).

The “Letters and Notes Collection” features correspondence from Emanuel to writers such as Gwendolyn Brooks, Ted Joans, Douglas Watson and others. Emanuel’s letters to Watson are perhaps the most in depth. In one letter, Emanuel refers to one of his most bitter poems, White-Belly Justice: A New York Souvenir, which addresses the extortion he experienced during his divorce. Read alongside his letters to Douglas Watson and others, this poem illuminates the conditions that laid the groundwork for Emanuel’s permanent departure from the United States. Other notes in the collection include his “Christmas Notes” that highlight his contributions to African-American literature. Marvin Holdt, a literary critic and Emanuel's close friend, described Emanuel as a writer who “makes no loud and dramatically uncompromising demands or claims... the truth, he would probably say, does not always have to be shouted. Tell it as it is, and you can speak softly; state the facts, and the facts will speak for themselves” (80). Even in holiday notes and personal reflections, Emanuel’s straight talk carries a clear message.

When there are no words, there are photographs. The “Photograph Collection” captures Emanuel’s travels in Europe, Asia, and Africa, as well as readings in Paris. Though they are stills, these images reveal Emanuel to be a man on the move. The collection also includes photographs taken by Emanuel. The tags “Le Barry,” the estate of Marie-France Plassard’s family, and “FESTAC 1977” are among those that appear most frequently.

Figure 2. An Imperfect Close-up of Emanuel at FESTAC '77.

The “Literary Criticism Collection” provides insight into Emanuel’s work as an editor and instructor. As general editor of the Broadside Critics Series, Emanuel developed the general format and vetted submissions from contributors. The series ended in 1975, a year before Broadside Press was transitioning to new ownership. Production declined in the closing years of Dudley Randall's inital period of leadership, as the press worked to stabilize its finances. (Emanuel “Letter to Ronald Walcott”). His textbook A Poet’s Mind provides insight into his approach to teaching. The book was influenced in part by his son, James Jr., who is the subject of some of the poems and appears in a photograph in the final chapter; the book also bridges familiar domains: Emanuel's poetry for and about children, his international travel, and poetry instruction for “ foreign students of English” (Watson “ James A. Emanuel” 116).

The “Miscellaneous Collection” fills in biographical gaps across Emanuel’s life. Items in the collection include a childhood sketch of a U.S. Marshal, his high school diploma, military ribbons, travel itineraries, and event flyers or programs. These materials align with Watson's observation that Emanuel motifs include “ travel scenes, celebrations of children and innocence, everyday events lucidly depicted, terrors remembered and traditions revered” (116).

Figure 3. James A. Emanuel's U.S. Army Ribbons.

The James A. Emanuel Project invites users to navigate multiple pathways through the selected archival materials. Emanuel took on many roles throughout his life, and to honor that complexity, the project offers multiple entry points for users: mini stories and oral histories for quick engagement, a documentary and readings for immersive learning, and essays and archival collections for in-depth research. Each medium retains its distinct form while pointing to a shared center: James A. Emanuel’s enduring legacy.

Works Cited

Emanuel, James A. "Letter to Douglas Watson." Dec. 1981. James A. Emanuel Papers, 1922–2018, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. MS Box 4, Folder 7.

Emanuel, James A. "Letter to Ronald Walcott." Jan. 1976. James A. Emanuel Papers, 1922–2018, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. MS Box 4, Folder 6.

Hilscher, Michelle C., and Gerald C. Cupchik. “Reading, Hearing, and Seeing Poetry Performed.” Empirical Studies of the Arts, vol. 23, no. 1, 2005, pp. 47–64. https://doi.org/10.2190/LGP5-Q4TM-D0U5-W029.

Holdt, Marvin. “James A. Emanuel: Black Man Abroad.” Black American Literature Forum, vol. 13, no. 3, Autumn 1979, pp. 79–85. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3041516. Accessed 21 May 2025.

“Quick Guide: Add and Embed a Resource.” CUNY Manifold. https://cuny.manifoldapp.org/read/add-and-embed-a-resource/section/6e7e3261-7475-4ad4-8b5c-113cbe6652c2. Accessed 29 Apr. 2025.

Smith, Virginia Whatley. “Jean Toomer Revisited in James Emanuel’s Postmodernist Jazz Haiku.” Cross-Cultural Visions in African American Literature, edited by Yoshinobu Hakutani, Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, pp. 81-108. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230119123_5.

Vincent-Arnaud, Nathalie. "Blue Note(s): James A. Emanuel (1921–2013)." Miranda, no. 11, 2015, doi:10.4000/miranda.7531.

Watson, Douglas. “James A. Emanuel.” Dictionary of Literary Biography. vol. 41, Gale, 1985, pp. 103–117.