James A. Emanuel: A Brief Bio

“The writing bug had...bitten me...for the Omaha Bee newspaper had sent me five dollars the previous year [1932] for my brief article ‘Going Up,’ in praise of construction at my favorite building, the local library, where I was beginning to spend countless evenings.”

From James A. Emanuel's A Force in the Field

In his autobiography, Emanuel reflects on his first payment as a writer, subsequent payments from the Omaha Bee-News would come later. He was twelve. The purchasing power of five dollars in 1932 was over one hundred dollars. This was extremely important during the Great Depression, especially since President Roosevelt did not sign the New Deal into law until 1933. It was during this period in the prairie town of Alliance, Nebraska that Emanuel’s mother, Cora, known as a stout woman by her grandson, James Smith, would reluctantly ask Emanuel and his brother Raymond to bring the coal along the train tracks that had falling from train cars back home. By then they had already removed the wood that lined the walls of the storage room in their home for firewood. In those challenging times of his youth, Emanuel managed to maintain all As on his report cards while working on Nebraskan farms.

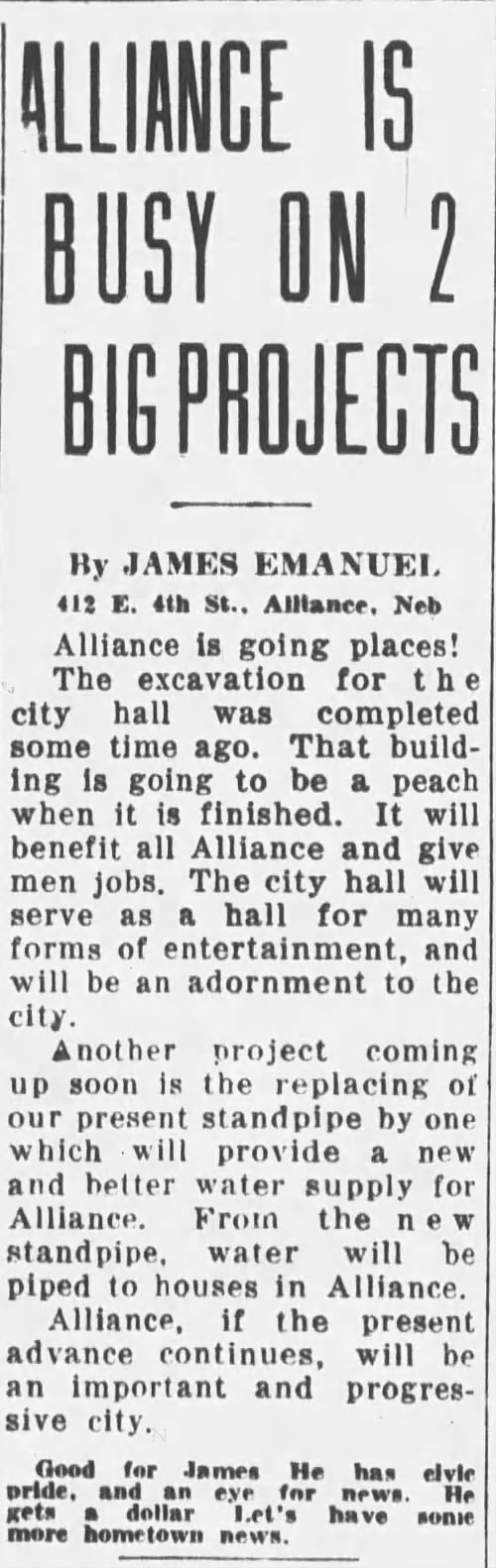

Figure 1. James Emanuel's article “Alliance Is Busy on 2 Big Projects” published in the Omaha Bee-News on Sunday, March 29, 1936.

Emanuel would take that work ethic with him when he left for Nebraska to join the Civil Service Corps in Wellington, Kansas to save money for college. There he published in the Chatterbox. While working in the bitter cold at a junkyard in Illinois and seeking better opportunities in the face of discrimination, Emanuel took the Federal Intelligence exam and had a near perfect score. Not too long afterward, he was offered a position in the civil service, and he took a position in Washington, DC.

![Typed letter from Benjamin O. Davis to James Emanuel, dated July 22, 1962. Davis thanks Emanuel for the birthday wishes. BRIGADIER GENERAL BENJAMIN O. DAVISU. S. A. (RET.)1721 S STREET, N.W.WASHINGTON 9, D. C.22 July 1962 Dear Mr. Emanual: I want to acknowledge with thanks your very kind note extending good wishes re my birthday. I feel rather flattered that you not only remembered it but that you took time out to let me know that you thought of it.Mrs. Davis joins me in thanking you and and extending our congratulations on your success in your chosen field. We both always felt that you would go places in your chosen field. In additionto thanking you we extend to you our wishes for your continued success. Mrs. Savis as an old schoolteacher is greatly pleased with the news of your success up to date and wish for you further advancees in your field. With kindest regards and thanks from both of us and good wishes, I am, Sincerely, [signature]B. 0. Davis.](https://cuny.manifoldapp.org/system/resource/1/3/7/1377cccb-fe7a-4594-a790-ed92cb74fa79/attachment/7a2487b6af21529948f7a7ea6b31cbf1.jpg)

Figure 2. Typed letter from Benjamin O. Davis to James Emanuel, dated July 22, 1962. Davis thanks Emanuel for the birthday wishes.

To be the confidential secretary for General Benjamin O. Davis, Sr., the first African American Brigadier General, grounded Emanuel in a familiar integrity, exposed him to the diversity of African American life, and prepared him to enlist in the army during World War II. These experiences would come through in his poem “Dark Soldier”; written in 1945. They also gave him access to a college education. He attended Howard University, studying English under famous professors like Sterling Brown and Alain Locke who were a part of “the indignant generation,” who ushered in Black literary criticism.

Emanuel continued to work part-time and full-time jobs to support himself and his wife Mattie Etha (Johnson) while he pursued a Master’s degree in English Literature at Northwestern University. The couple had one child, a son, James, Jr. while Emanuel was completing his doctorate in American Literature at Columbia University. As Emanuel managed his homelife and predatory landlords, he also published poems, but his most dedicated work, as a graduate student, was the study of Langston Hughes’s short stories. Hughes gave Emanuel access to his home, papers, and mentorship. Emanuel’s dissertation would become Langston Hughes (1967), the first book of scholarship written on Hughes’s work. Emanuel goal was to solidify the study of African American literature, and he spent his career doing just that.

Figure 3. Langston Hughes is interviewed by James A. Emanuel on January 29, 1965.

Emanuel co-edited the anthology Dark Symphony: Negro Literature in America (1968) with Theodore L. Gross, understanding that anthologies provide access to a wide variety of writers, genres, and styles that would contribute to a canonization of African American writers. Emanuel taught African American Literature, advocating for and teaching the first Black Poetry course at City University of New York (CUNY), City College where he would remain his entire academic career (1957 to 1984). He also taught Black Literature in Europe—at the University of Grenoble, France as a Fulbright Professor; at the University of Toulouse, France as a visiting Professor; and at the University of Warsaw, Poland as a Fulbright Professor.

![Image Description:

This is an official identification document from the University of Warsaw (Uniwersytet Warszawski). On the left side, it features a black-and-white passport-style photograph of James A. Emanuel, with several red ink stamps partially overlapping the photo and document text. The photo includes his signature below it, and surrounding text in Polish appears to validate his credentials and affiliation.

The right side contains handwritten and typed details confirming Emanuel’s status as a visiting or affiliated professor at the University of Warsaw. The document is dated October 1975, and includes official stamps and signatures authenticating it.

The background of the document contains an intricate yellow floral security design.

Transcript (translated and transcribed where appropriate):

UNIWERSYTET WARSZAWSKI

Warszawa, Krakowskie Przedmieście 26/28

(pečędź podłużna wystawcy)

Legitymacja Nr. 1291/75

James

(nazwisko)

Emanuel

(imię – imiona)

prof. nadzwyczajny U.S. Neofillogii

(stanowisko i tytuł służbowy)

w Uniwersytecie Warszawskim

Warszawa, dn. października 75

[Official red seal stamp]

Signature (left side):

James A. Emanuel

(podpis posiadającego legitymację)

Text above photo (in Polish):

Uprawnia do przejazdów koleją państwową według list kartkowych dla pracowników państwowych

(Translation: 'Entitles the holder to travel on the state railway according to list tickets for state employees.')

Valid for the year issued: 1975–76](https://cuny.manifoldapp.org/system/resource/7/e/1/7e145412-f2d2-4cc7-b961-cc624683777e/attachment/e6bac5c480f067c541b7a987759b84d7.jpg)

Figure 4. James A. Emanuel University of Warsaw Identification Card.

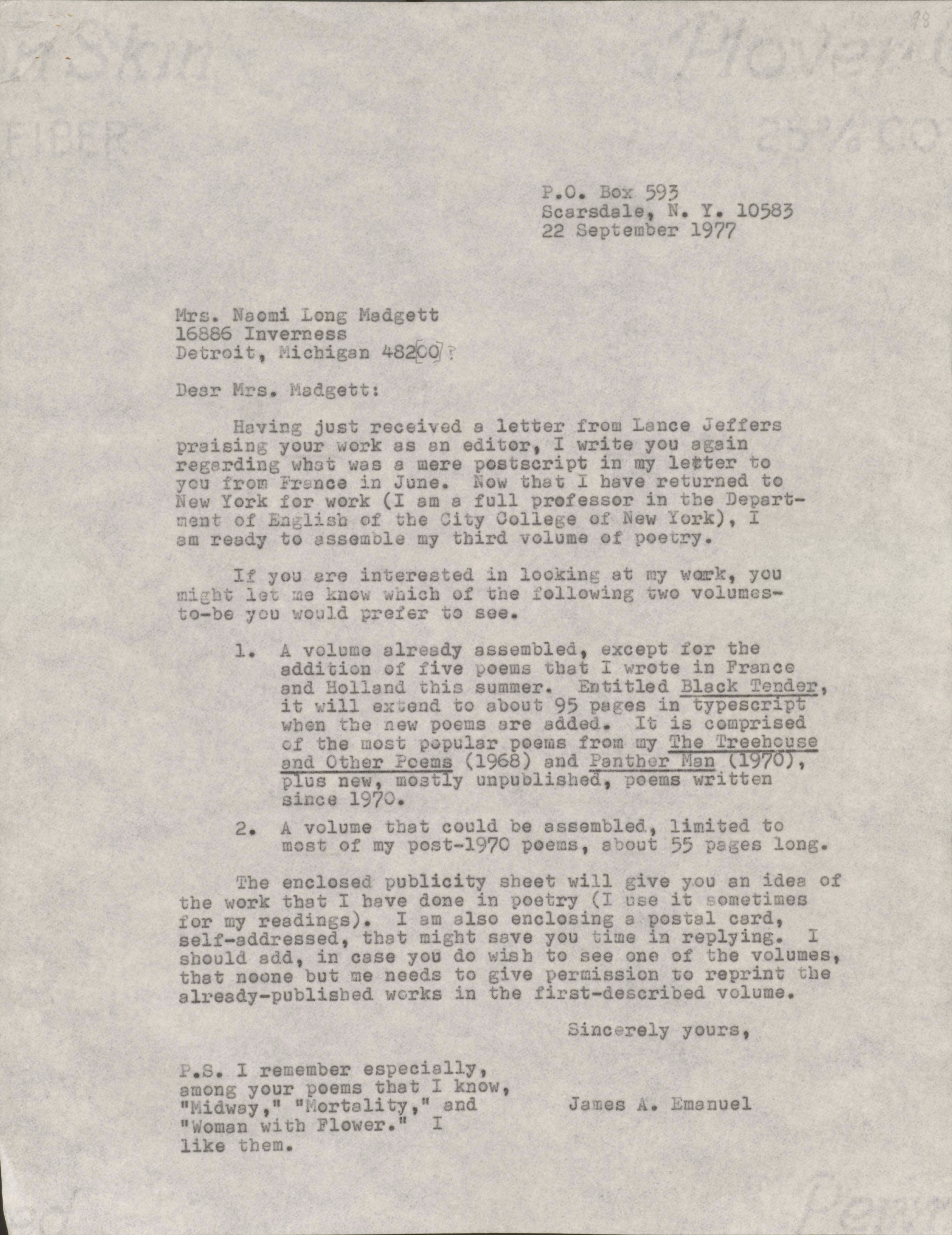

It was Emanuel's relationship with Dudley Randall and Naomi Long Madgett both poets and publishers that was the most enduring and demonstrative of Emanuel's commitment to African American literature and its grassroots institutional structures. Independently and collectively, Randall's company Broadside Press and Madgett's company Lotus Press, later to become Broadside Lotus Press, published Emanuel's writing for four decades. Emanuel's first poetry collection The Treehouse and Other Poems (1968), whose title was recommended by Langston Hughes, and his second collection Panther Man (1970), were published by Broadside Press. Treehouse contains Emanuel's most anthologized poem “Emmett Till” and other poems that still resonate with contemporary readers such as “After the Accident.” The book opens with the dedication “For my son James, Just as he is” and includes many poems about children using simple and captivating language. In Panther Man, Emanuel again focuses on youth yet with an intention to “attack the cowardly authoritarianism,” writing that the collection “owes its existence to the only people whom I tend to respect as a group: young people” (Panther Man 7). Emanuel was inspired by youth such as his son, James, Jr., the 4th Grade students at Prospect School in Long Island School, his students at City College, and Mark Clark and Fred Hampton, two brothers and Black Panthers who were murdered in their sleep by Chicago Police. The poem for Clark and Hampton, “Panther Man,” inspired the title of the collection. After publishing the two poetry collections with Broadside Press, Emanuel collaborated with Dudley Randall on the Broadside Critics Series as general editor. This series extended the mission of the press beyond poetry and into Black literary criticism.

Figure 5. Typed letter to Naomi Long Madgett from James Emanuel, dated September 22, 1977. He gives her two options for publishing a new volume of his work.

Emanuel's five subsequent poetry collections Black Man Abroad: The Toulouse Poems (1978), A Chisel in the Dark: Poems Selected and New (1980), The Broken Bowl: New and Uncollected Poems (1983), Deadly James and Other Poems (1987), and Whole Grain: Collected Poems, 1958-1989. were published by Madgett's Lotus Press. The eight-year gap between publishing Panther Man and Black Man Abroad: The Toulouse Poems was due to many changes in Emanuel's life, including divorce and international travel. In the preface of Black Man Abroad, Emanuel acknowledges the “transitional nature” of the collection, mentioning a year teaching behind the Iron Curtain (7). However, it is the poem “For Alix, Who Is Three” and the collection's dedication that reveal the origins of the collection. “For Alix” is the second poem in the collection. It is dedicated to the three-year old daughter of Emanuel's friend. She inspires Emanuel and gives him the “clé,” the key to write again. Emanuel notes in his autobiography A Force in the Field (1995) that reading this poem brings tears to his eyes. The origins of Black Man Abroad is also revealed in its dedication to “Marie-France [Plassard],” a librarian and lifelong friend of Emanuel who he met at the University of Toulouse. She and her mother provided their family home in Condom, France (known affectionately as Le Barry) as a respite and writing retreat for Emanuel. Le Barry is noted often at the top of Emanuel's draft poems that make up the five collections published between 1978 and 1989. During this period, Lotus Press was essential to Emanuel's publishing and the Plassard's home was essential place for Emanuel's writings.

Figure 6. “M[arie]-F[rance] and I [James A. Emanuel] on terrace wall at Le Barry JAE 3.04.07.”1

Emanuel published his last two books with Broadside Press: Jazz from the Haiku King (1999) and The Force and the Reckoning (2001). Jazz from the Haiku King is a culmination of Emanuel adherence to the haiku form's strict discipline with the spirit of collaboration. The poems in this collection and their derivatives were performed live with orchestras, bands, and solo musical accompaniment with musicians such as Chansse Evans and Noah Howard. The French translations were written by Jean Migrenne, Emanuel's friend and French translator, and occasionally performed live by Migrenne and Marie-France Plassard. The works were also exhibited as engravings by Godelieve Simons, Emanuel's friend and multidisciplinary artist. The latter work, The Force and the Reckoning is an autobiography and poetry collection. The Force contains autobiographical content from Emanuel's first and second autobiogaphies Snowflakes and Steel: My Life as a Poet (1981) and A Force in the Field (1995). The poetry in The Force and the Reckoning appeared in Jazz from the Haiku King, Emanuel's chapbook Reaching for Mumia: 16 Haiku (1995), and his collected poems Whole Grain.

Emanuel's poetry was catalyzed by the dimensions of his life: the prairies of his childhood, military service, marriage and fatherhood, the Civil Rights and Black Power movements, music, travel, and the intellectual discourse of his time. Even in retirement as an expatriate in Paris, he continued to write, teach, and share his knowledge of African American literature with international audiences. From his Montparnasse apartment, where he lived and wrote for decades, James A. Emanuel was a force until his death in 2013.

“The Force”

With life, always Force:

strong arm to work, heart to fight,

will to risk, do right.

-The Force and the Reckoning, xiii

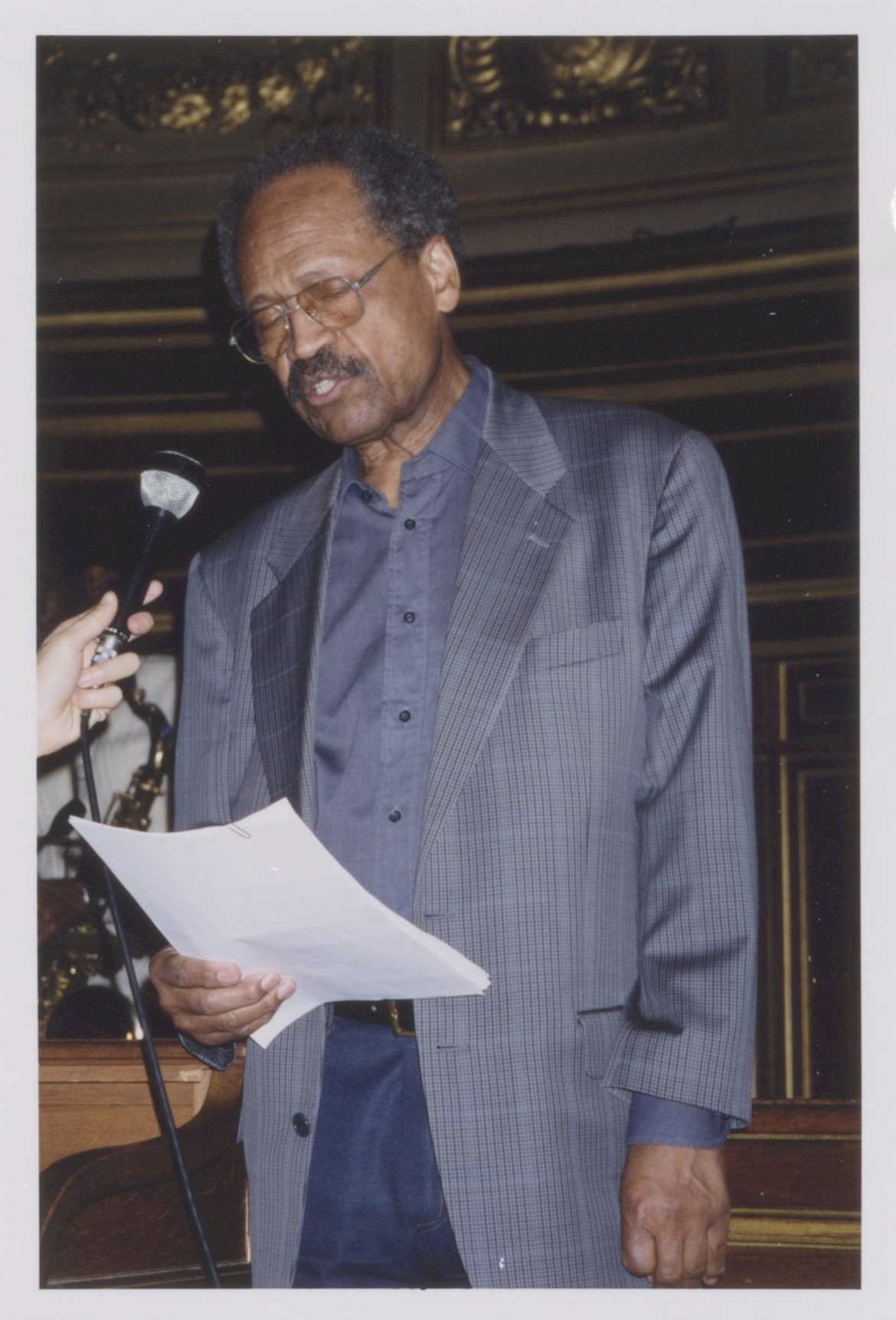

Figure 7. “Me [James A. Emanuel], reading my poetry at the Sorbonne, 28 Oct. 2000 JAE, Paris 11.05.2007.”

Emanuel, James A. “A Force in the Field.” Contemporary Authors Autobiography Series, vol. 18, Gale, 1994.

—. Black Man Abroad: The Toulouse Poems. Detroit: Lotus Press, 1978.

—. Panther Man. Detroit: Broadside Press, 1970.

—. The Force and the Reckoning. Detroit: Lotus Press, 2001.

—. The Treehouse and Other Poems. Detroit: Broadside Press, 1968.

- James A. Emanuel recorded dates in a day-month-year format. For this photo and others, I use his original descriptions. He typically signed as “JAE” and included the date: in this case, April 3, 2007. ↩