Mini Story: Noah Howard (Middle Passage)

Between May 17 and 19 2001, James Emanuel met with Noah Howard in his Altsax Music Studio in Tervuren, an affluent international municipality near Brussels, to record what would become the Middle Passage album. Emanuel wrote to Howard in February of 2000 about the potential collaboration, writing "If you could consider making a recording with me...we could rehearse doing-the-do jazzily. I know you might be too busy to consider this, but give it a thought when you can" ("James Emanuel's letter to Noah Howard" 1). It would be a little over a year before they would record. The album was a cultural amalgamation featuring Emanuel’s recitations of his jazz haiku from his book Jazz from the Haiku King and Howard’s jazz improvisational saxophone riffs. A beautifully performed collaboration, the poems are haiku, a strict Japanese poetic form consisting of seventeen syllables that “deals with the discipline of image and careful attention to language” while using images to capture its essence (Laryea and Moore 167). Emanuel’s haiku centers on the experiences of African Americans, using the Middle Passage as a focal point. Collectively, the form and theme draw attention to the restriction and discipline placed upon the Africans who were captured and transported on slave ships. The jazz music played by Howard on saxophone and expressed in Emanuel’s haiku signal survival as “continuous creation, though a mix of form and improvisation” (Howard 122). Middle Passage is the interplay of poetry and music, a homage to African American cultural poetics, an expression of blues notes harkening the traumatic experience of being transported across the Atlantic, and “jazz music unified improvisationally through deep listening” (Howard 39).

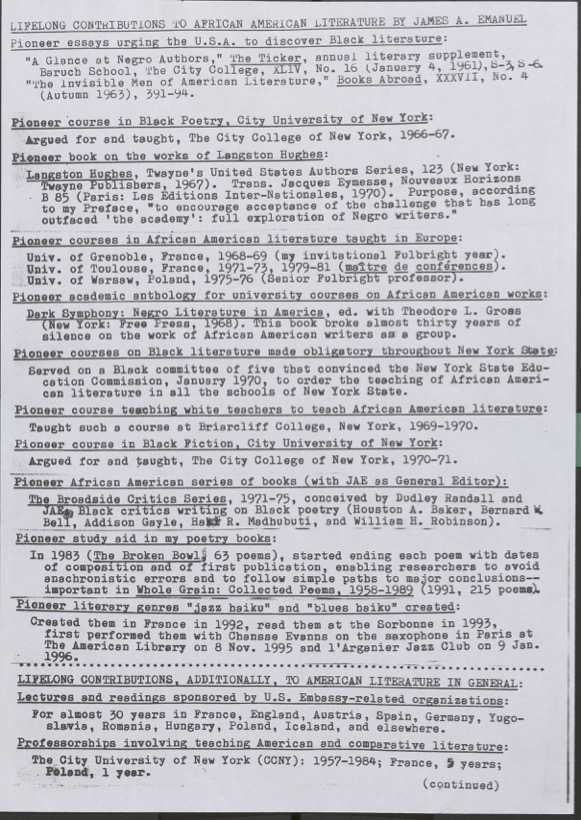

![James Emanuel letter to Noah Howard Home fax: 55 bis, bd du Montparnasse+33-1-45493266 75006 Paris FRANCE 7 February 2000Noah HowardAltsax MusicRozenlaan 7B-3030 TervurenBELGIUMDear Noah, Although the French quit expressing NewYear’s greetings when January ends, I departfrom them in saying HAPPY NEW YEAR--even afterthe groundhog has had his chance to say it. I hope that the enclosed JAZZ from the HaikuKing (which Godelieve Simons of Brussels has auto-graphed too) will remind you of our pleasant visitto your place last year. Although Broadside Pressdid not--perhaps could not-- follow my plan andkeep the integrity of Godelieve’s engravings inthe book in Section VI, “Jazz Meets the Abstract,” the publisher things enough of the book, just pub-lished in November, to submit it for the PulitzerPrize. But that big prize requires the influence andand inside track. If you can consider making a recording withme, based on these jazz-and-blues-and-gospel haikuthat are a new literary genre, maybe you can choosethose haiku (and longer poems, perhaps) that wouldbest fit saxophone music. Having your list, I could read them onto a cassette for you to let youknow my style, poem by poem. I could compose a “gig sheet,” as I call them (winding up usuallywith ten or more sheets for a whole program [did I send you a program that I made up for Chansse?]; then, after you suggest changes and educate me con-cerning your recording-room technology, we couldrehearse doing-the-do jazzily. I know you might be to busy to consider this, but giveit a thought when you can. Cordial regards, J EmanuelP.S. I enclosed, too, my 1999 “Literary Happenings” sheet (I have 8 earlier ones, each just as long) to give you an idea of my recent track record.](https://cuny.manifoldapp.org/system/resource/5/2/8/528b27f4-f2a4-41e9-9fcd-78038dea8808/attachment/dab45c6f4498cd92b236b84e2ae31157.jpg)

Figure 1. Typed letter from James Emanuel to Noah Howard, dated February, 7, 2000. He sends Noah a copy of "JAZZ from the Haiku King" and wishes to collaborate on a jazz record.

On their album, Howard and Emanuel, self-described as “Noah Howard of the World” and James Emanuel the pioneer, convey their consistent openness to collaboration and innovation in their respective forms. While they met in Europe, they shared other connections. Both men were African Americans who volunteered in the army, lived in New York City during the 1960s, traveled extensively to pursue their art, and lived in Europe for more than thirty years. All the while, they kept African American expressive cultures as a driving trope in their artistic practice.

Figure 2. First page of the document in which James Emanuel lists his pioneering contributions to African American Literature.

Howard, born in New Orleans, Louisiana, lived his life following the music. His mother and stepfather exposed him to the music of Umm Kulthum. His cousin was the manager of pioneering musician Fats Domino. While he served in the army, he played in the band, and after his honorable discharge, he travelled in pursuit of the “music in [his] soul.” While his dedication to music began in Los Angeles, he followed the music, shortly thereafter, to San Francisco and New York. It was in New York City, inspired by Coltrane and learning from Sun Ra, where Howard began to compose and develop his own sound (Howard 33). He began “sound painting,” which is first fully represented in his record Patterns (1971). After years of collaborating, conducting, recording, and even working briefly as a booking agent, Howard traveled to Kenya, where he felt a profound connection to being back in the homeland, Africa. He stayed in Kenya a year after meeting his wife, Lieve Fransen.

Figure 3. James A. Emanuel records poems for Middle Passage (2001), backed by Noah Howard playing saxophone.

“As the first in my family to make this voyage back to my community,” Howard writes in his autobiography, “I was filled with emotion and started to cry—thinking about all those before me who didn’t survive the middle passage and slave trade” (Howard 82). We hear this from Howard in Middle Passage. His emotions colored the sounds in his collaboration with Emanuel. “I try to get the melody and rhythm of the poem and bring my sax sound as close as possible to the colors and vibrations” (Howard 42 - 3).

Figure 4. Oral History Interview with Dr. Lieve Fransen, Noah Howard's widow.

Works Cited

Emanuel, James A. "James Emanuel's letter to Noah Howard." 2000. BOX 13 FOLDER 13 "H" MISCELLANEOUS, 1971, 1999–2000, James A. Emanuel papers, 1922–2018. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Howard, Noah. Music in My Soul. Buddy's Knife Jazzedition, 2011.

Laryea, Doris Lucas, and Lenard Duane Moore. “The Open Eye of Lenard Duane Moore: An Interview.” Obsidian II, vol. 11, no. 1/2, 1996, pp. 159–84. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44502784. Accessed 29 Apr. 2025.

- James A. Emanuel recorded dates in a day-month-year format. For this photo and others, I use his original descriptions. He typically signed “JAE” and included the date, in this case 3 April 2007. ↩