Poem #1: “Little Old Black Historian”

While a student at Howard University, James Emanuel benefite from John Hope Franklin's mentorship. Franklin welcomed him into his office and showed him a draft of what would become From Slavery to Freedom: A History of American Negroes, a seminal work on Black history in America. Many years later, Emanuel wrote a letter to Franklin to share the progress of his career. That same year, Emanuel wrote the poem “Little Old Black Historian (For John Hope Franklin),” which exemplifies ancestor acknowledgment.

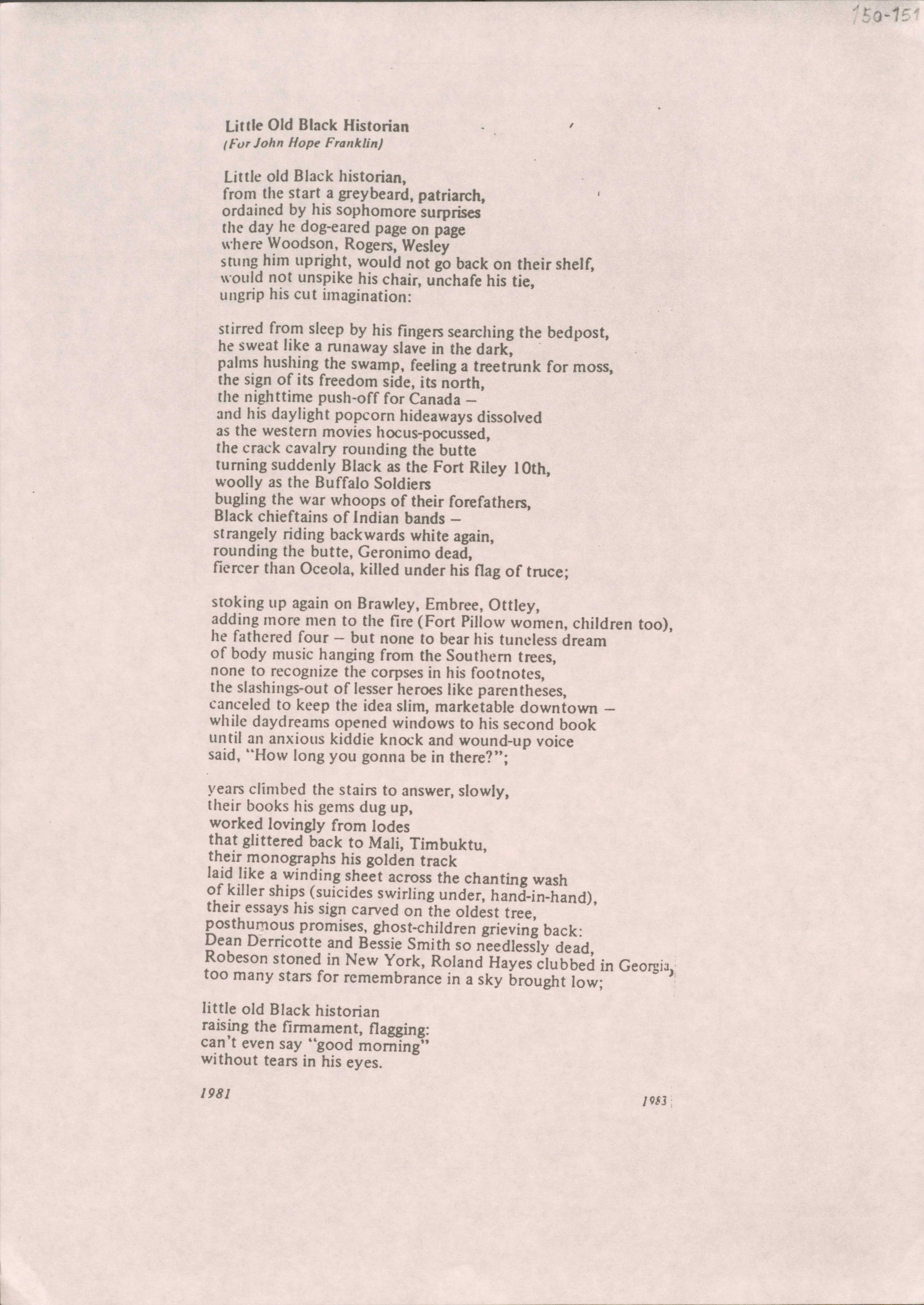

Figure 1. Poem written by Emanuel in 1983 in to John Hope Franklin. In it, Emanuel draws parallels between the quest for education through literacy to that of freedom from slavery.

In the poem, Emanuel portrays Franklin as a disciplined scholar who is shaped by the intellectual legacy of his predecessors: historians, such as Carter G. Woodson, founder of Black History Month; Joel Augustus Rogers, whose research focused on the African diaspora; and Charles H. Wesley, President of Wilberforce University and Central University (Ohio). These scholars “stung him upright, would not go back on their shelf, / would not unspike his chair, unchafe his tie, / ungrip his cut imagination” (6–8). Emanuel portrays Franklin as physically and intellectually compelled by the writings of those who came before him. The imagery of Franklin being "stung," "spiked," and "gripped" conveys the weight of historical responsibility and the rigorous demands of engaging with the work of past scholars.

Franklin’s evolution as a scholar is connected to ancestral acknowledgment and guidance. As discussed in the Knarrative’s episode “Remembering: John Hope Franklin - Born #OnThisDay (January 2, 1915 - March 25, 2009),” Gregory Carr notes that Franklin’s research was initially focused on North Carolina and Reconstruction, and he identified as a southern historian before he pivoted toward African-American history (2:03 – 2:43). “Little Old Black Historian” reflects the transition of Franklin’s research interest through the line “ordained by his sophomore surprises” (3). It is Franklin’s move into African American history--despite his grounding in Southern historical study--that defines him as a Black historian, placing him under the tutelage of the Black historians whose work set the terms for his own.

“Little Old Black Historian,” however, extends beyond Franklin’s book knowledge. The poem illustrates how he embodies African-American history in his dreams. Franklin’s physical and emotional immersion in the past is a type of ancestral acknowledgment. He is “stirred from sleep by his fingers searching the bedpost, / he sweat like a runaway slave in the dark, / palms hushing the swamp, feeling a tree trunk for moss” (9–11). These lines suggest a subconscious connection to historical memory; Franklin’s body reenacts the struggles of those who came before him. Furthermore, as Franklin conducts his research, he is confronted with the deception of Western historical narratives. He witnesses “the crack cavalry rounding the butte / turning suddenly Black as the Fort Riley 10th” (16–17) and “Black chieftains of Indian bands— / strangely riding backwards white again” (19–20). These images reflect the revisionist nature of Franklin's work; in his ancestor acknowledgment, Franklin exposes the erasure and misrepresentation of Black figures in American history. Through this blend of historical research and ancestral presence, the poem portrays Franklin’s writing process as more than an intellectual endeavor—it is an embodied act of researching, reclaiming and rewriting/righting the past.

In the third stanza, ancestor acknowledgment is strengthened through obtaining ancestral wisdom. The poem suggests that Franklin’s knowledge of Black history was built by literature written by ancestors. This is similar to Toni Morrison’s statement that “It seems to me interesting to evaluate Black literature on what the writer does with the presence of an ancestor. […] There is always an elder there. […] [T]hey provide a certain kind of wisdom” (61-2). For Franklin, in the poem, this wisdom is quoted, referenced, and footnoted. Emanuel notes additional scholars of Black history such as Benjamin Griffith Brawley, author of A Short History of the American Negro (1921); Elihu Embree, a European-American abolitionist who published the first abolitionist newspaper Manumission Intelligencier; and Roi Ottley, a journalist who authored New World A-Coming: Inside Black America (1943); these historians are mentioned alongside the memory of the men, women, and children massacred at Fort Pillow during the Civil War (24 – 26). From the books, monographs, essays, and legacies of these historians, Franklin “dug up” gems, laid a rich path, and signposted (36, 39, 42). Emanuel frames Franklin’s career as being built upon the “lodes” of earlier historians. Yet this acknowledgment of intellectual ancestors also suggests the overwhelming nature of the work still to be done.

Emanuel writes that Franklin had “fathered four” editions of From Slavery to Freedom (though it was actually five at the time of Emanuel’s writing) (27). Today, the book has reached ten editions, with the most recent being published in 2021. Yet like any archive of lived experience, none of these editions fully capture the depth of Franklin’s vision for ancestral acknowledgment. Emanuel writes:

…none to bear the tuneless dream

of body music hanging from Southern trees,

none to recognize the corpses in his footnotes,

the slashings-out of lesser heroes like parentheses,

canceled to keep the idea slim, marketable downtown—

while daydreams opened windows to his second book

until an anxious kiddie knock and wound-up voice

said, “How long you gonna be in there?”; 26 – 33

These lines highlight how Franklin’s work was constrained by commercial demands. His manuscript was growing too long, which forced him to omit certain “lesser heroes”in order to adhere to publishing limitations. The need to make the book “slim” and “marketable downtown” meant that recognition of the lynched (“body music hanging from Southern trees”), the forgotten (“the corpses in his footnotes”), and the obscure (“slashings-out of lesser heroes”) could not be fully realized. The poem mourns these losses, describing them as “too many stars for remembrance in a sky brought low” (46). Like Atlas, Franklin—the “little old Black historian”—bears the heavy burden of “raising the firmament, flagging” (48). Franklin “can’t even say ‘good morning’ / without tears in his eyes” (49 – 50). Emanuel’s poem positions Franklin as both a scholar and a weary witness to the weight of ancestor acknowledgment as he writes African-American history.

Works Cited

Emanuel, James A. “Little Old Black Historian (For John Hope Franklin).” From “The Chopping Block (Selected Poems), Draft, 1988 (2 of 2).” James A. Emanuel papers, 1922 - 2018. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. MS Box 4 Folder 27

Knarrative. “Remembering: John Hope Franklin - Born #OnThisDay (January 2, 1915 - March 25, 2009).” , YouTube, 3 Jan. 2022, www.youtube.com/watch?v=pChHiX_yAg0.

Morrison, Toni. “Rootedness: The Ancestor as Foundation.” What Moves at the Margin: Selected Nonfiction, edited by Carolyn C. Denard, University Press of Mississippi, 2008, pp. 56–64.