Skip to main contentResource added

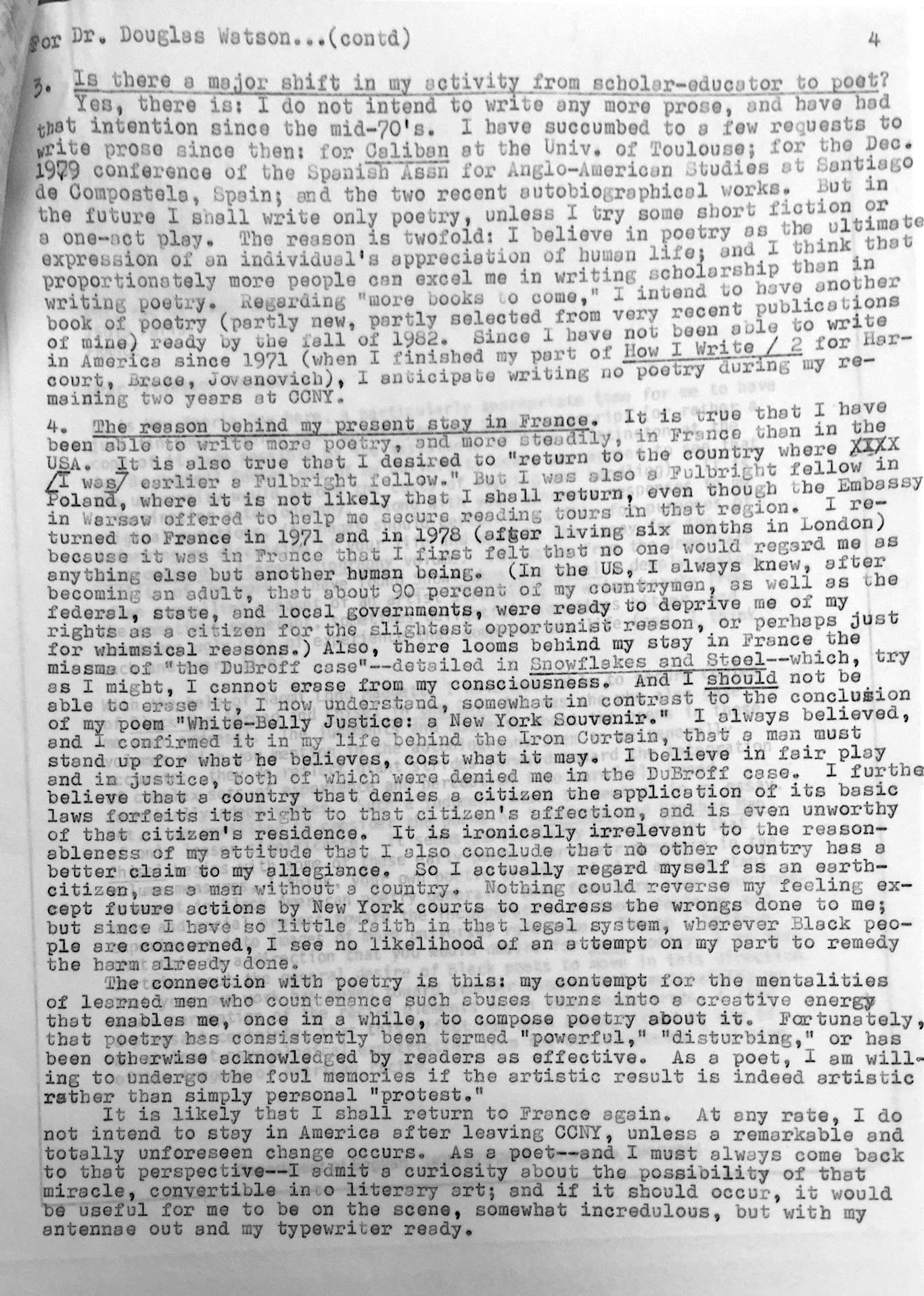

Second Letter to Douglas Watson December 1981 (page 4 of 4)

Full description

Typed letter to Douglas Watson from James Emanuel, dated December 3, 1981. Emanuel responds to an earlier letter from Watson and speaks about his influences and writing practices (Page 4).

Comments

to view and add comments.

Annotations

No one has annotated a text with this resource yet.

- typeImage

- created on

- file formatjpg

- file size1 MB

- container titleJames A. Emanuel Papers

- creatorJames A. Emanuel

- issueBox 4 Folder 7, Watson, Douglas, 1981-1993

- rightsJames A. Emanuel Estate

- rights holderJames A. Emanuel Estate

- version1981