Notes

Inclusive Environmental Design for Promoting Physical Activity of Low-Income Group

Si Zhang, School of Architecture, Harbin Institute of Technology; Key Laboratory of Cold Region Urban and Rural Human Settlement Environment Science and Technology, Ministry of Industry and Information Technology

Guangtian Zou, School of Architecture, Harbin Institute of Technology; Key Laboratory of Cold Region Urban and Rural Human Settlement Environment Science and Technology, Ministry of Industry and Information Technology

Shuyu Liu, School of Architecture, Harbin Institute of Technology; Key Laboratory of Cold Region Urban and Rural Human Settlement Environment Science and Technology, Ministry of Industry and Information Technology

Abstract

With the rapid development of urbanization in China, more and more low-income group enter urban life and their physical activity has an important impact on quality of their life which is an important index of urbanization quality. Statistics show that low-income group has the lowest physical activity, but there are few related researches in China. In terms of environmental design, public environment and facilities play a more important role on low-income group life compared with middle- and high-income group.

This paper seeks to deal with inclusive environmental design for promoting physical activity of low-income group by using inclusive architectural design model. Based on the analysis of the living environments and physical activity characteristics of low-income group, and combined with relevant research achievements, the paper puts forward inclusive environmental design guidelines for promoting physical activity of low-income group, including perceived environmental elements design, participatory public facilities construction, supportive community place molding, and sustainable urban environmental renewal.

With "Healthy China 2030" program, it is a new subject with positive significance and great value to study how to promote the health activity of low-income group by design. This paper helps to provide environmental design basis in China and inclusive environmental support for the realization of "Healthy China 2030".

Keywords: Low-income group; Physical activity for health; Physical activity; Environmental inclusiveness; Inclusive environmental design

Introduction

With the rapid development of urbanization in China, more and more low-income group enter urban life. Low-income group is a vulnerable group and their quality of life is an important index of urbanization quality. Studies show that there is a significant positive correlation between physical activity and QOL(Berger & Tobar, 2012; Gill et al., 2013). Globally insufficient physical activity is identified to be the fourth leading risk factor for global mortality, causing an estimated 3.2 million deaths worldwide(WHO, 2014), and has also triggered a series of global economic problems(Ding et al., 2016). More noteworthy is that low-income group has the lowest physical activity of all people.

Research on low-income group in China is dominated by residential behaviors, employment behaviors and consumer behaviors, while behavioral research on their physical activity is particularly insufficient at present. In terms of environmental design, public environment and facilities play a more important role on low-income group life compared with middle- and high-income group(Ellder, Larsson, Sola, & Vilhelmson, 2018). Therefore, with "Healthy China 2030" program, it is a new subject with positive significance and great value to study how to promote the health activity of low-income group by design.

Active Living by Design is a health oriented architectural environment design theory originated from the U.S.(Health & Services, 1996). In 2014, "promotion of physical activity" was also regarded as one of the important health design goals in AIA’s design and health initiative(AIA, 2014), which refers to encouraging exercise, recreation and other daily activity that lower the risk of cardiovascular disease and other health problems.

In order to provide an equitable built environment for all and actively realize "Healthy China 2030", how to improve the physical activity of low-income group through environmental design is a significant and far-reaching research issue.

Aims

This paper seeks to deal with inclusive environmental design for promoting physical activity of low-income group has threefold aims. The first, is to explore inclusive values of built environment of low-income group. The second, is to identify physical activity characteristics of low-income group for inclusive environmental design. The third, is to propose inclusive environmental design guidelines for promoting physical activity of low-income group.

Methodology

Methodology

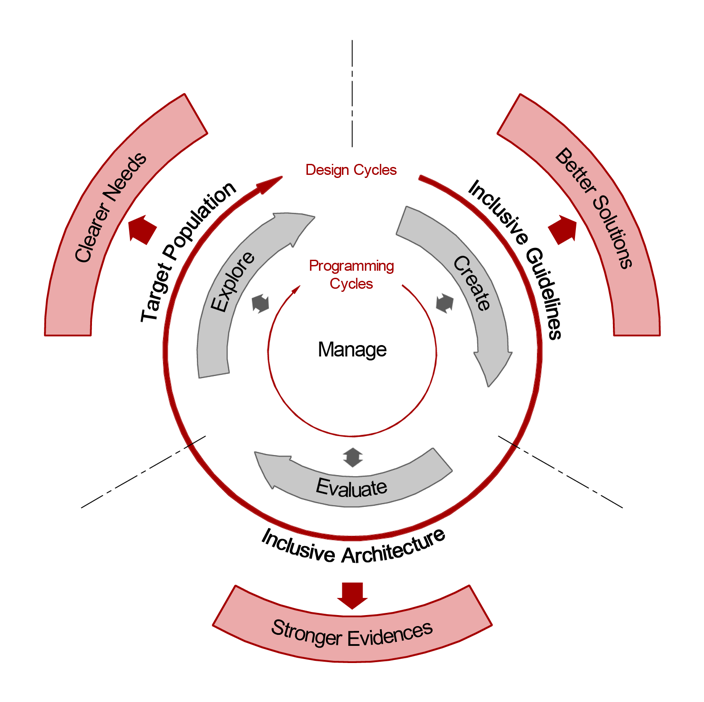

The methodology basis of this study is inclusive architectural design model(Zhang, Zou, & Liu, 2018) (Fig.1) which is updated model of original inclusive design model(Keates, 2005). In this model, the main steps are put forward based on environmental behavior science, including environmental analysis and assessment, behavioral analysis of target population, and strategy generation for problem solving, which is finally realized through architectural programming and design.

The British Standards Institute (2005) defines inclusive design as: “The design of mainstream products and/or services that are accessible to, and usable by, as many people as reasonably possible ... without the need for special adaptation or specialized design.” Inclusive design focuses on the diversity of people and the impact of this on design decisions(Clarkson, Coleman, Hosking, & Waller, 2007). After more than 20 years of development, inclusive design has developed a complete set of theoretical models in the methods and procedures and has been applied to many design areas, ranging from industrial design to architectural design, with different emphasis in each design(John Clarkson & Coleman, 2015; Waller, Bradley, Hosking, & Clarkson, 2015). In the field of environmental design, inclusive aims to embrace the mainstream and vulnerable group with equitable built environment, give the vulnerable group an equitable living space, which will minimum affect the normal life of the mainstream group.

Living environments of low-income group

Creating and evaluating an inclusive environment is the starting and end point of inclusive architectural planning and design cycles. The first step is analysis of the current situation of the environment, establish inclusive value to clarify directions and to find problems.

Living environment plays a decisive role in residential health, especially in low-income group. The attributes of physical environments is a driving force of the underlying mechanisms(Rauh, Landrigan, & Claudio, 2008). In different social backgrounds, the living conditions of low-income group in different countries are different, but some problems are common. Low-income housing clusters tend to be located in more densely-developed central city locations(Dawkins, 2013). Physical housing problems declined in the past decades, but some low-income group still face problems such as damaged structures and inadequate facilities(Kingsley, 2017). Environmental problems were common and more than half of homes had 3 or more exposure-related problems(Adamkiewicz et al., 2014).

In China, urban low-income group mainly live in "village-in-city" old high-density residential buildings, affordable housing in low-rent housing(Xu, 2006). According to interviews with low-income families in Beijing, their demands for living environments are to get more space for family members for independent living, dining, learning and washing, and they hope to have supporting facilities and willing to live in their own familiar environment(Zhou & Wang, 2009). They strive for more living space for their families and perhaps they would rather live in polluted areas, noisy areas, and areas with inconvenient traffic, and unconsciously pay the price of health. Because of the realistic predicament, it is even more extravagant to let the low-income group lead a healthier life through their living environment when the basic living space is difficult to guarantee.

With "Healthy China 2030" program, China government put health in the strategic position of priority development. As an important environmental guarantee for improving citizens' health, urban area should inclusively provide all residents with a positive healthy environment. Health-friendly activities provided through urban facilities should serve more people to a greater extent. To improve the inclusiveness of city and the sharing of urban resources, we need not only policy and economic support, but also design enhancement from the perspective of environmental design.

Physical activity characteristics of low-income group

The target population of inclusive environmental design is low-income group. The next step is to summarize and analyze behavior characteristics of the target population and physical activity characteristics of low-income group, and summarize the problems, explore the causes of the problems, providing ideas for problem solving.

There is an association between income and physical activity, higher income was associated with higher self-reported physical activity for both genders(Kari et al., 2015; Kim & So, 2014). However, compared with high-income group, low-income group face a more formidable combination of personal and environmental barriers to being physically active(Beyers & Brown, 2008). This difference in physical activity caused by family income level occurs not only in adults, but also in children. Among children of different age group, research indicates that children in the lower-income group engaged in vigorous physical activity less often than children in the higher-income group(Fox, Hamilton, & Lin, 2004).

Insufficient physical activity is a key reason that many people in low-income residential areas are overweight or obese, both of which increase the risk for diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure and stroke. Evidence suggests that people from low-income group are more difficult to identify and successfully recruit to general population interventions(Bull, Dombrowski, McCleary, & Johnston, 2014). Limited access to parks, long distances to sports facilities, poor transportation services, poor neighborhoods and traffic conditions, all of which limit people from being physically active, are often distinctive characteristics of low-income urban neighborhoods(Frumkin, Frank, & Jackson, 2004). It will be very helpful to improve the health of low-income group if active physical activity of low-income group motivated or lead by environmental design, including physical activity improved passively.

Inclusive environmental design guidelines for promoting physical activity of low-income group

For finding better solutions, what should be taken step is to create inclusive environmental design guidelines which based on the environmental characteristics and behavior description of target population.

The living environment of low-income group is characterized by high-density centralized housing, poor facilities and exposure-related environmental problems. However, compared with the physical environment, they are faced with more affordable problems due to economic reasons(Kingsley, 2017). At the same time, due to education, health awareness and other reasons, low-income group lack conscious, time-consuming, energy or money-consuming health activities. Therefore, the environmental design of promoting physical activity of low-income group mainly depends on reasonable facility design, architectural design and urban design with minimizing or without increasing economic costs.

Under the background of the current social imbalance development, inclusive environmental design pays attention to vulnerable group. As an important part of social vulnerable group, low-income group is the target population of inclusive environmental design research. Inclusiveness has multi-dimensional and complex connotation and there is different emphasis in the conditions of target population and different environments. In this paper, inclusive design can be analyzed as follows: perceived environmental elements design, participatory public facilities construction, supportive community place molding, and sustainable urban environmental renewal.

Perceived environmental elements design

For environmental elements design, environmental awareness should be actively improved through environmental elements design to promote physical activity of low-income groups. In a certain area, a higher perceived environment can promote physical activity of low-income adults(Jauregui et al., 2017). Perceived environmental factors include regional functions diversity, streets connectivity, safety of walking and riding, aesthetic and comfort living environment. Compared with adults, children can perceive more abundant environmental factors, and are affected in positive way either. In addition to practicality, safety and beauty, the rich and interesting space experience can be included, which also help to achieve the design goal of promoting physical activity. A good practice as example is the piano key staircase design of a subway entrance in Stockholm, Sweden(Fig.2). When people walked by, the speaker will play different tones which can generate joyful and surprise (Peeters, Megens, van den Hoven, Hummels, & Brombacher, 2013). More importantly, such a design does not add extra space costs, and it not only adds fun to the short traffic experience, but also promotes social life and active living.

Participatory public facilities construction

For public facility design, environmental participation should be actively improved through public facility design to promote physical activity of low-income groups. The inactive behavior of low-income group is related to the lack of public facilities(Floyd, Taylor, & Whitt-Glover, 2009). For adolescents, their physical activity will be carried out more often with teachers or parents(Cohen, Morgan, Plotnikoff, Hulteen, & Lubans, 2017). Participatory public facilities include open green place, parks providing picnic place, sports facilities in communities or schools, and active sites for teachers and parents. Larger green place is more conducive to promoting physical activity for low-income group, so the scattered small green space can be properly centralized(Greer, Castrogivanni, & Marcello, 2017). Public facilities for parents' participation include not only for accompany, supervise and rest, but also behavioral interaction. For example, MRC designs Expression Swing(Fig.3), which improves the participation and interaction of parent-child activities, which adding an attractive target activity into parks to improve health activities.

Supportive community place molding

For community place design, environmental supportiveness should be actively improved through community place design to promote physical activity of low-income groups. Community is not only a spatial definition, but also a connection and belonging in psychology, which plays an important role in promoting physical activity of low-income group(Fan, Wen, & Kowaleski-Jones, 2014). For the complexity meaning, community has impact on environment, behavior and psychology. Therefore, supportive community place molding is multifaceted, including the improvement of infrastructure, the education and dissemination on health activities, and the health plan. The Mueller community in Austin(Fig.4) is a good example of a supportive community. The openness of the public space, the connectivity with the adjacent parks, and the diversity and selectivity of community activities have promoted health living. Part of the green space is designed into gardening area, which creating a unique life scene, providing planting activities, promoting neighborhood communication, and promoting people's healthy lifestyle by environmental design.

Sustainable urban environmental renewal

For urban environmental design, environmental sustainability should be actively improved through urban environmental renewal to promote physical activity of low-income groups. A healthy, sustainable, equitable urban environment is the premise for healthy development of vulnerable group which including low-income group. The sustainable environmental renewal, which aims at promoting health activities, should pay attention to the links between adjacent regions in expansion, especially the greenway and the shade facilities(Karner, Hondula, & Vanos, 2015). At the same time, the formulation of policies should also take promotion of physical activity for residents into account. Take Olympic host city as example, hosting the Olympic Games will have a positive impact on the health activities of low-income group, even at Rio, where facilities are not reused well(Sousa-Mast et al., 2017). Olympic Park in Beijing(Fig.5) links the venues, provides a large public area for health activities, and hosts a number of themed marathon activities. These initiatives have contributed to the health activities of urban residents, including low-income group.

Conclusions

Based on the inclusive architectural design model, this paper discusses the living environment of low-income group and the physical activity characteristics of low-income group. The result indicates that the level of physical activity of low-income group is insufficient, and their living environment is not conducive to more physical activity. By combing the results of relevant research, this paper puts forward several design proposals aimed at improving the physical activity of low-income group, including perceived environmental elements design, participatory public facilities construction, supportive community place molding, and sustainable urban environmental renewal. Promoting physical activity of low-income group through environmental design is a brand-new research topic in China. With the undertaking of "Healthy China 2030" program, more empirical studies under this framework, such as on the evaluation of living environment of low-income group, physical and mental health of low-income group, will be carried out continuously.

Reference

Adamkiewicz, G., Spengler, J. D., Harley, A. E., Stoddard, A., Yang, M., Alvarez-Reeves, M., & Sorensen, G. (2014). Environmental conditions in low-income urban housing: clustering and associations with self-reported health. American journal of public health, 104(9), 1650-1656.

AIA. (2014). AIA’s design and health initiative. Retrieved from https://www.aia.org/pages/3461-aias-design-health-initiative

Berger, B. G., & Tobar, D. A. (2012). Physical activity and quality of life: Key considerations. Handbook of Sport Psychology, Third Edition, 598-620.

Beyers, M., & Brown, J. (2008). Life and death from unnatural causes: health and social inequality in Alameda County: CAPE unit of the Alameda County Public Health Department.

Bull, E. R., Dombrowski, S. U., McCleary, N., & Johnston, M. (2014). Are interventions for low-income group effective in changing healthy eating, physical activity and smoking behaviours? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ open, 4(11), e006046.

Clarkson, P., Coleman, R., Hosking, I., & Waller, S. (2007). Inclusive design toolkit: Engineering Design Centre, University of Cambridge, UK.

Cohen, K. E., Morgan, P. J., Plotnikoff, R. C., Hulteen, R. M., & Lubans, D. R. (2017). Psychological, social and physical environmental mediators of the SCORES intervention on physical activity among children living in low-income communities. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 32, 1-11. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.05.001

Dawkins, C. (2013). Exploring the spatial distribution of low income housing tax credit properties: BiblioGov.

Ding, D., Lawson, K. D., Kolbe-Alexander, T. L., Finkelstein, E. A., Katzmarzyk, P. T., Van Mechelen, W., . . . Committee, L. P. A. S. E. (2016). The economic burden of physical inactivity: a global analysis of major non-communicable diseases. The Lancet, 388(10051), 1311-1324.

Ellder, E., Larsson, A., Sola, A. G., & Vilhelmson, B. (2018). Proximity changes to what and for whom? Investigating sustainable accessibility change in the Gothenburg city region 1990-2014. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 12(4), 271-285. doi:10.1080/15568318.2017.1363327

Fan, J. X., Wen, M., & Kowaleski-Jones, L. (2014). An ecological analysis of environmental correlates of active commuting in urban US. Health & Place, 30, 242-250. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.09.014

Floyd, M. F., Taylor, W. C., & Whitt-Glover, M. (2009). Measurement of park and recreation environments that support physical activity in low-income communities of color: Highlights of challenges and recommendations. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 36(4, Suppl), S156-S160. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.009

Fox, M. K., Hamilton, W., & Lin, B.-H. (2004). Effects of food assistance and nutrition programs on nutrition and health. Food Assistance and Nutrition Research Report, 19(3).

Frumkin, H., Frank, L., & Jackson, R. J. (2004). Urban sprawl and public health: Designing, planning, and building for healthy communities: Island Press.

Gill, D. L., Hammond, C. C., Reifsteck, E. J., Jehu, C. M., Williams, R. A., Adams, M. M., . . . Shang, Y.-T. (2013). Physical activity and quality of life. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, 46(Suppl 1), S28.

Greer, A. E., Castrogivanni, B., & Marcello, R. (2017). Park use and physical activity among mostly low-to-middle income, minority parents and their children. Journal of Physical Activity & Health, 14(2), 83-87. doi:10.1123/jpah.2016-0310

Health, U. D. o., & Services, H. (1996). Physical activity and health: A report of the Surgeon General. Retrieved from Atlanta, GA: http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/sgr/pdf/execsumm.pdf

Jauregui, A., Salvo, D., Lamadrid-Figueroa, H., Hernandez, B., Rivera, J. A., & Pratt, M. (2017). Perceived neighborhood environmental attributes associated with leisure-time and transport physical activity in Mexican adults. Preventive Medicine, 103, S21-S26. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.11.014

John Clarkson, P., & Coleman, R. (2015). History of Inclusive Design in the UK. Appl Ergon, 46 Pt B, 235-247. doi:10.1016/j.apergo.2013.03.002

Kari, J. T., Pehkonen, J., Hirvensalo, M., Yang, X., Hutri-Kähönen, N., Raitakari, O. T., & Tammelin, T. H. (2015). Income and physical activity among adults: evidence from self-reported and pedometer-based physical activity measurements. PloS one, 10(8), e0135651.

Karner, A., Hondula, D. M., & Vanos, J. K. (2015). Heat exposure during non-motorized travel: Implications for transportation policy under climate change. Journal of Transport & Health, 2(4), 451-459. doi:10.1016/j.jth.2015.10.001

Keates, S. (2005). BS 7000-6: 2005 Design management systems. Managing inclusive design. Guide.

Kim, I.-G., & So, W.-Y. (2014). The relationship between household income and physical activity in Korea. Journal of physical therapy science, 26(12), 1887-1889.

Kingsley, G. T. (2017). Trends in housing problems and federal housing assistance. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Peeters, M., Megens, C., van den Hoven, E., Hummels, C., & Brombacher, A. (2013). Social stairs: taking the piano staircase towards long-term behavioral change. Paper presented at the International Conference on Persuasive Technology.

Rauh, V. A., Landrigan, P. J., & Claudio, L. (2008). Housing and health. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1136(1), 276-288.

Sousa-Mast, F. R., Reis, A. C., Vieira, M. C., Sperandei, S., Gurgel, L. A., & Pühse, U. (2017). Does being an Olympic city help improve recreational resources? Examining the quality of physical activity resources in a low-income neighborhood of Rio de Janeiro. International Journal of Public Health, 62(2), 263-268. doi:10.1007/s00038-016-0827-7

Waller, S., Bradley, M., Hosking, I., & Clarkson, P. J. (2015). Making the case for inclusive design. Appl Ergon, 46 Pt B, 297-303. doi:10.1016/j.apergo.2013.03.012

WHO. (2014). Global Status Report on non-communicable diseases. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/148114/9789241564854_eng.pdf;jsessionid=DA659ED0F1D49749925FA1DB8BD951DB?sequence=1

Xu, G. (2006). The Residence Design Studies For Low-income Persons in Our Country. Hunan University.

Zhang, S., Zou, G., & Liu, S. (2018). Research on Inclusive Design of Waiting Room in Healthcare. Paper presented at the ISAIA 2018. The 12th International Symposium on Architectural Interchanges in Asia, Pyeongchang Alpensia, Gangwon, Korea.

Zhou, Y., & Wang, F. (2009). Research on Residential Demand of Low-income People in Beijing and Its Enlightenment to Low-rent Housing Architectural Design. Architectural Journal(8), 6-9.