The 1917 El Paso “Bath Riots”

Excerpted from Tala Khanmalek, “‘Wild Tongues Can't Be Tamed’: Rumor, Racialized Sexuality, and the 1917 Bath Riots In the US-Mexico Borderlands,” Latino Studies vol. 19, 3 (2021): 334-357 and Ranjani Chakraborty, “The Dark History of ‘Gasoline Baths’ at the Border,” Vox, July 29, 2019.

ABSTRACT

On 28 January 1917, a group of women led by seventeen-year-old Carmelita Torres defied quarantine orders at the US-Mexico border, where Mexican-heritage people were required to undergo delousing. According to local and national coverage of the protest, rumors that United States Public Health Service officials had photographed women in the nude ignited what would come to be known as the Bath Riots. Newspaper reports highlighted the racialized and sexualized construction of Mexican women as disease carriers in need of regulation and public health photographs of the El Paso disinfection plant.

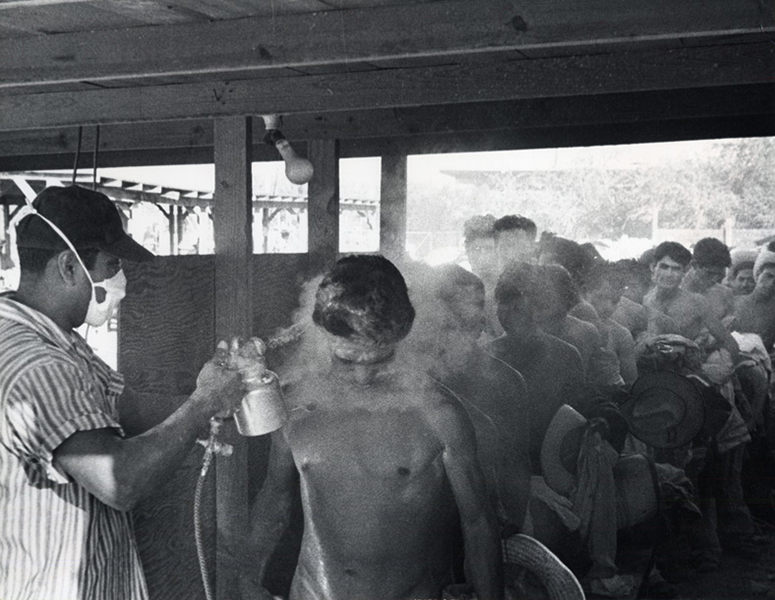

Contract Mexican laborers being fumigated with the pesticide DDT in Hidalgo, Texas, in 1956. Leonard Nadel, Courtesy National Museum of American History

INTRODUCTION

On 28 January 1917, seventeen-year-old Carmelita Torres led a group of women who refused to comply with quarantine orders at the US-Mexico border, igniting what would come to be known as the Bath Riots. The quarantine orders—issued by Senior Surgeon Claude Connor Pierce with the full support of El Paso Mayor Tom Lea—required Mexican-heritage people to undergo a lengthy, highly toxic delousing procedure before crossing the Rio Grande River via the Santa Fe Street International Bridge that connects El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua. Authorized under the pretense of typhus prevention, compulsory delousing transformed the bridge into a barrier for Mexican migrants. Unlike Chinese and southern and Eastern European migrants, Mexican migrants had previously crossed the border unrestricted and were exempt from restrictions put forth in the 1917 Immigration Act. Mexican women, many of whom lived in Ciudad Juárez and worked in El Paso as domestics and laundresses, were disproportionately affected by public health control over the border.

According to the El Paso Morning Times, rioting began when United States Public Health Service (USPHS) officials ordered the women to get off the streetcars that transported them to the bridge every day and enter the newly refitted disinfection plant on the other end.3 A closer look at newspaper coverage of the Bath Riots reveals that Carmelita Torres and her peers were not just protesting Pierce’s unprecedented border quarantine. More precisely, the Bath Riots resulted partially due to “rumors among servant girls” that officials had photographed women in the nude while subjecting them to the final stage of delousing: spraying the body with a kerosene-based chemical solution. [1]

Both scholarly and popular literature have frequently cited the Bath Riots as a singular and spectacular moment of resistance to the USPHS. Yet it is viewed as just that, a moment with no lasting effects on public health control over the border, especially since compulsory delousing continued for years to come, even as part of the Bracero Program (1942–1965). Specifically, little attention has been paid to allegations that officials had photographed women in the disinfection plant when in fact these rumors evidence the buried traces of another story.

Published in 1987, Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands La Frontera had a watershed impact on late twentieth-century feminist of color literature, women’s studies, and Latinx studies inside and outside the academy. The book begins with seven mixed-genre chapters in which Anzaldúa develops a theory of borderlands as not only a specific geographic locale—the US-Mexico border where she was raised—but also an embodied landscape “present wherever two or more cultures edge each other,” producing an open wound.[2] A “third country” nevertheless emerges from this liminal space defined by violence, including a distinctly bordered language, subjectivity, agency, and consciousness that undermine patriarchal nation-centric paradigms.[3] In short, Anzaldúan borderlands theory situates the site of wounding squarely within the racialized and sexualized body, which simultaneously conditions alternative ways of being and knowing.

Taking up Anzaldúa to explore strategies of biomedical containment and subversion at the US-Mexico border makes public health legible as a contested site of Latinx othering. Public health was pivotal to early twentieth-century forms of governance, empire-building, and the making of Latinx difference. However, analytical concepts that privilege race—such as “racialized medicalization”—obscure the ways in which sexuality and other categories of difference emerged in relation to racial formation through policies enacted on the body.[4] Practices like delousing, which the USPHS mandated only at the US-Mexico border, shaped and were shaped by the racialized sexuality of working-class Mexican women and are the historical antecedents of current policies targeting the Latinx population, especially in militarized border zones.

The first headline of the El Paso Morning Times coverage reads, “Order to Bath Starts Near Riot among Juarez Women: Auburn-Haired Amazon at Santa Fe Street Bridge Leads Feminine Outbreak. [5] The report repeatedly references the crowd’s rate of growth, allegedly reaching several thousand by late morning. Here again, quantitative accounting portrays white El Pasoans as helplessly outnumbered victims of an uncontrollably growing force. “One of the street car motormen, finally making his way back to the American side, emerged from the mob with half a dozen women clinging to him, endeavoring to drag him down,” it states.[6] The narrow escape of a single motorman from Juárez depicts El Paso as a safe haven under siege. He manages to cross the border, though not unscathed; the attackers use his body as their host, dragging him down as they enter the United States. Ubiquitous images like this one transform the women from targets of state management to agential embodiments of disease. In short, Mexican women degrade the nation’s social and moral values in the process of infecting white male citizens. The details of the report, as well as its headline dubbing the protest a “feminine outbreak,” point to the simultaneously racialized and sexualized construction of “superspreaders” in what literary critic Priscilla Wald calls an “outbreak narrative.”[7]

The report refers to the protest as an “anti-cleanup demonstration,” further linking delousing procedures to the regulation of racialized sexuality.[8] As early as the 1880s, El Paso conducted cleanup campaigns to displace sex workers already confined to certain areas of the city by law. Meanwhile, Ciudad Juárez was literally and figuratively developed into an amusement park where social and moral values could be transgressed without consequence. In turn, this rebranded Juárez reinforced hypersexualized representations of Mexican women who, in the report, mercilessly overwhelm American troops while Mexican troops join in their quote “disgusting exhibition.”[9] Disgust expresses a moral judgment directly connected to late nineteenth-century anti-prostitution and social purity movements. In other words, refusing to be cleaned up is a sign of immorality that also undermines Juárez as a site of touristic consumption.

Even though “crowds of spectators” in El Paso watched the “excitement” of “a seething Latin mob scene” from only a few feet away, the women successfully prevented white tourists from crossing the bridge.[10] In fact, immigration officials barred entry for the day, stating that it was a “bad day for Americans” with “the rack [sic] track, gambling houses, and amusement places of Juárez” closed.[11] The report not only emphasizes injury to white bodies with objects like stones, but also the destruction of streetcars as well as other automobiles:

As soon as an automobile would cross the line the girls would absolutely cover it. The scene reminded one of bees swarming. The hands of the feminine mob would claw and tear at the tops of the cars. The glass rear windows of the autos were torn out, the tops torn to pieces and parts of the fittings, such as lamps and horns, were torn away.[12]

This passage points to the pervasive conflation of human, animal, and microbial populations, and simultaneously conveys a challenge to the promise of continental expansion reproduced in automobile travel to Mexico. The women take hold of car parts as weapons, reappropriating the vehicles—in some cases, the very vehicles that transport them every day—to block the Santa Fe Street Bridge. Similarly, automobiles made to transport middle-class white families purposefully malfunction at the hands of Torres and her peers. For one day, the scripting of manifest destiny is forestalled in their hometown of Juárez.

The report goes beyond situating disease squarely within the racialized and sexualized body and instead portrays the women as disease vectors, or nonhuman organisms that transmit disease. At the border, USPHS discourse, practices, and policies that had initially treated Mexican-heritage people as disease carriers then targeted these people as disease vectors, or nonhuman organisms that transmit disease. This more complex and multispecies construction of difference and disease goes beyond defining disease in racial terms and reveals another way in which “the dialogical interplay between empire and neocolony played out across the Rio Grande.”[13] Torres is an “auburn-haired Amazon,” leading “Mexican Amazons.” The racialized and sexualized construction of Indigenous as well as Black femaleness undergird Torres’s discursive othering in the report. As Simone Browne explains, Blackness is central to surveillance as both a discursive and material practice that enforces the boundary line of borders as well as bodies. The ways in which the report conceptualizes the protesting women is part of why their claims cannot be anything but false. As racialized and sexualized nonhuman organisms in need of regulation, violence against the protesting women becomes impossible to imagine. Rather, the women’s “impulse was to injure and insult Americans as much as possible without actually committing murder.”[14]

The women “kept up a continuous volley of language aimed at the immigration and health officers, civilians, sentries and any other visible American,” the report proclaims. The report continues, “Small stones were thrown, but the missiles were little more dangerous than the language.” Although the report exaggerates the weaponization of language by Mexican women, it also suggests that they had been “insulted” and photographed in the disinfection plant. The second headline of the El Paso Morning Times report reads, “Rumors among Servant Girls That Quarantine Officers Photographed Bathers in the Altogether Responsible for Wild Scenes.”[15] …

Although Torres and the riots briefly shut down the border, the campaign would continue for decades and even go on to inspire Nazi scientists.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- How did rumors and racial stereotypes contribute to the enforcement of "gasoline baths" at the US-Mexico border in 1917? Consider how these perceptions of "racialized sexuality" and disease shaped public attitudes and policy decisions during this period.

- In what ways do the 1917 Bath Riots reflect broader issues of power, control, and resistance in border enforcement practices?

NOTES

1 “Order to Bath Starts Near Riot among Juarez Women,” El Paso Times, January 29, 1917.

2 Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands La Frontera: The New Mestiza, (San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 1987), 20.

3 Anzaldúa, Borderlands La Frontera, 25.

4 Natalie Molina, “Borders, Laborers, and Racialized Medicalization: Mexican Immigration and U.S. Public Health Practices in the Twentieth Century,” In Precarious Prescriptions: Contested Histories of Race and Health in North America eds. Laurie B Green, John Mckiernan-González, and Martin Summers, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), 167–184.

5 “Order to Bath Starts Near Riot among Juarez Women.”

6 “Order to Bath Starts Near Riot among Juarez Women.”

7 Priscilla Wald, Contagious: Cultures, Carriers, and the Outbreak Narrative (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008), 4-5.

8 “Order to Bath Starts Near Riot among Juarez Women.”

9 “Order to Bath Starts Near Riot among Juarez Women.”

10 “Order to Bath Starts Near Riot among Juarez Women.”

11 “Order to Bath Starts Near Riot among Juarez Women.”

12 Alexandra Stern, Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in Modern America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 52.

13 “Mexican Amazons Injure 2 Soldiers in Bridge Rush,” New-York Tribune, January 30, 1917.

14 Simone Browne, Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015).

15 “Order to Bath Starts Near Riot among Juarez Women.”

BIBGLIOGRAPHY

Acuna, Rodolfo. Occupied America: A History of the Chicanos. New York: Longman, 2002.

Gomez-Quinones, Juan. Chicano Politics: Reality and Promise, 1940-1990. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1990.

Horowitz, Ruth. Honor and the American Dream: Culture and Identity in a Chicano Community. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1983.

Romo, David Dorado. Ringside Seat to a Revolution: An Underground Cultural History of El Paso and Juarez, 1893-1923. El Paso, TX: Cinco Puntos Press, 2005.

Skerry, Peter. Mexican Americans: The Ambivalent Minority. New York: Free Press, 1993.

Telles, Edwards E., and Vilma Ortiz. Generations of Exclusion: Mexican Americans, Assimilation, and Race. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2008.